What can the final vote on the Brewers stadium package tell us about Wisconsin politics?

"The political dynamics that shaped the Senate vote on shared revenue provide us with a reasonably good guide to the politics of the stadium deal."

The Recombobulation Area is a ten-time Milwaukee Press Club award-winning weekly opinion column and online publication written, edited and published by longtime Milwaukee journalist Dan Shafer. Learn more about it here.

This column is by Phil Rocco, associate professor of political science at Marquette University. Rocco is a regular contributor at The Recombobulation Area

Whatever else the Wisconsin State Legislature may be, it is a graveyard of ideas about how to spend public money. The legislature has long ruled out expanding Medicaid, creating paid family leave, legalizing marijuana, replacing lead pipes, or adding universal background checks for firearm purchases.

But on Tuesday of this week, a bipartisan vote in the Wisconsin State Senate guaranteed that the state will be allocating hundreds of millions of dollars in tax revenue to help support a Major League Baseball franchise valued at $1.6 billion.

In a state where divided government often seems to yield gridlock over so many important policy issues, the Senate votes on AB 438 and AB 439 (the two bills that make up the stadium package) offer something of a puzzle. Not only are the final votes close — both bills passed with an identical three-vote margin — they also resist easy explanation via reference to Senators’ party labels. Republicans were split on both measures 11–11, and Democrats supported each 8–3.

So what explains the final vote tallies, and what can it tell us — if anything — about the structure of Wisconsin politics?

To analyze the passage of the stadium legislation, I developed a simple model to account for the roll-call votes on the two bills. Given the complexities of the issues involved in the vote, my intention was not to understand all the issues that mattered to the 33 members of the Wisconsin Senate. Rather, given that the vote split both Republican and Democratic delegations, I wanted to identify a few variables that would help to predict a relatively large share of votes on the measure.

To begin, I included a variable indicating whether members represented districts in the “five county” Milwaukee area — an area that, of course, funded the initial construction of what was then Miller Park through the five-county stadium tax. These senators could be expected to oppose the deal, albeit for different reasons. Some senators representing parts of Milwaukee County could be expected to oppose the final deal at least in part because the city and county of Milwaukee are the only units of local government responsible for co-financing the stadium package. More than 20% of project financing will come from these city and county contributions. Senators representing districts in the four counties surrounding Milwaukee had other reasons to oppose the measure, ranging from dissatisfaction with the overall level of public spending to the absence of key provisions in the bill, including but not limited to a tax on tickets to Brewers home games.

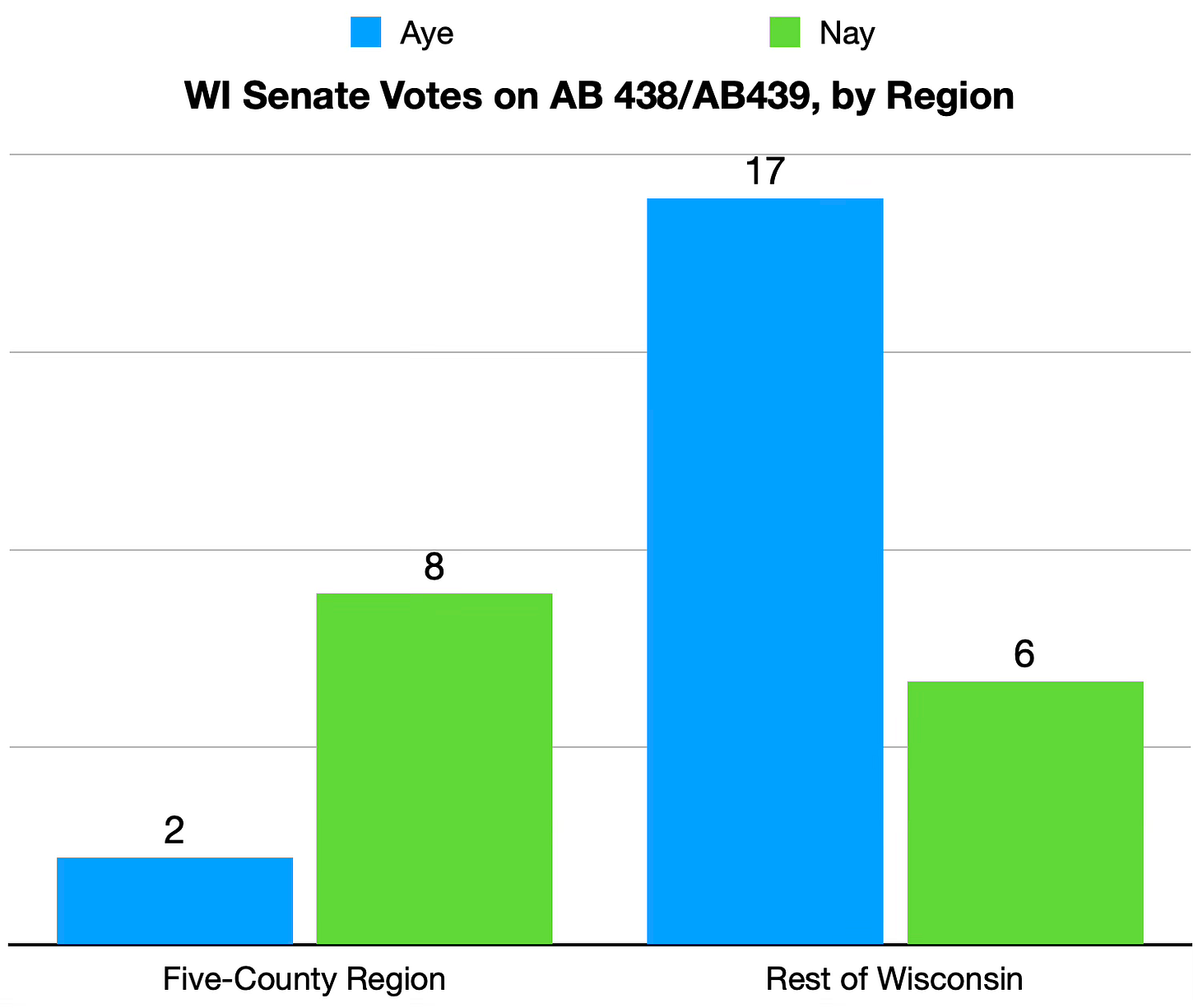

A cross-tabulation (see figure below) of votes by region confirms this intuition. Of the 10 senators representing districts located in the five-county region, only two voted in favor of the stadium bills, while 17 of 23 senators from the rest of Wisconsin supported the package.

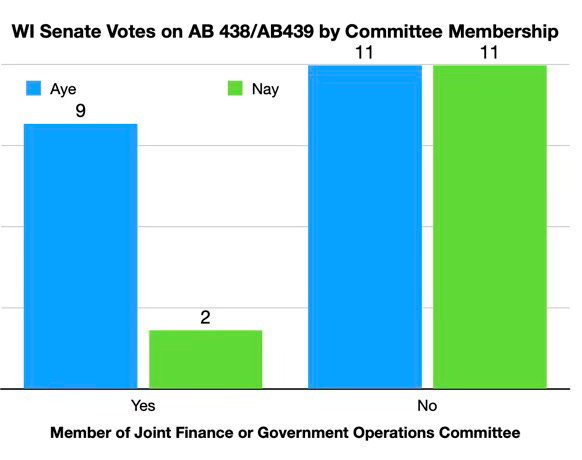

Second, I included a variable indicating whether senators were members of either of the two committees to which the legislation was referred: the Government Operations Committee and the Joint Committee on Finance. Both committees favorably reported the legislation to the floor of the Senate on bipartisan lines. I thus expected committee membership would be associated with a positive vote on the passage of AB438 and AB439.

Again, a simple cross-tabulation of votes on the bills and committee membership seems to confirm this suspicion. Members of both committees overwhelmingly supported the measure while non-members were evenly split.

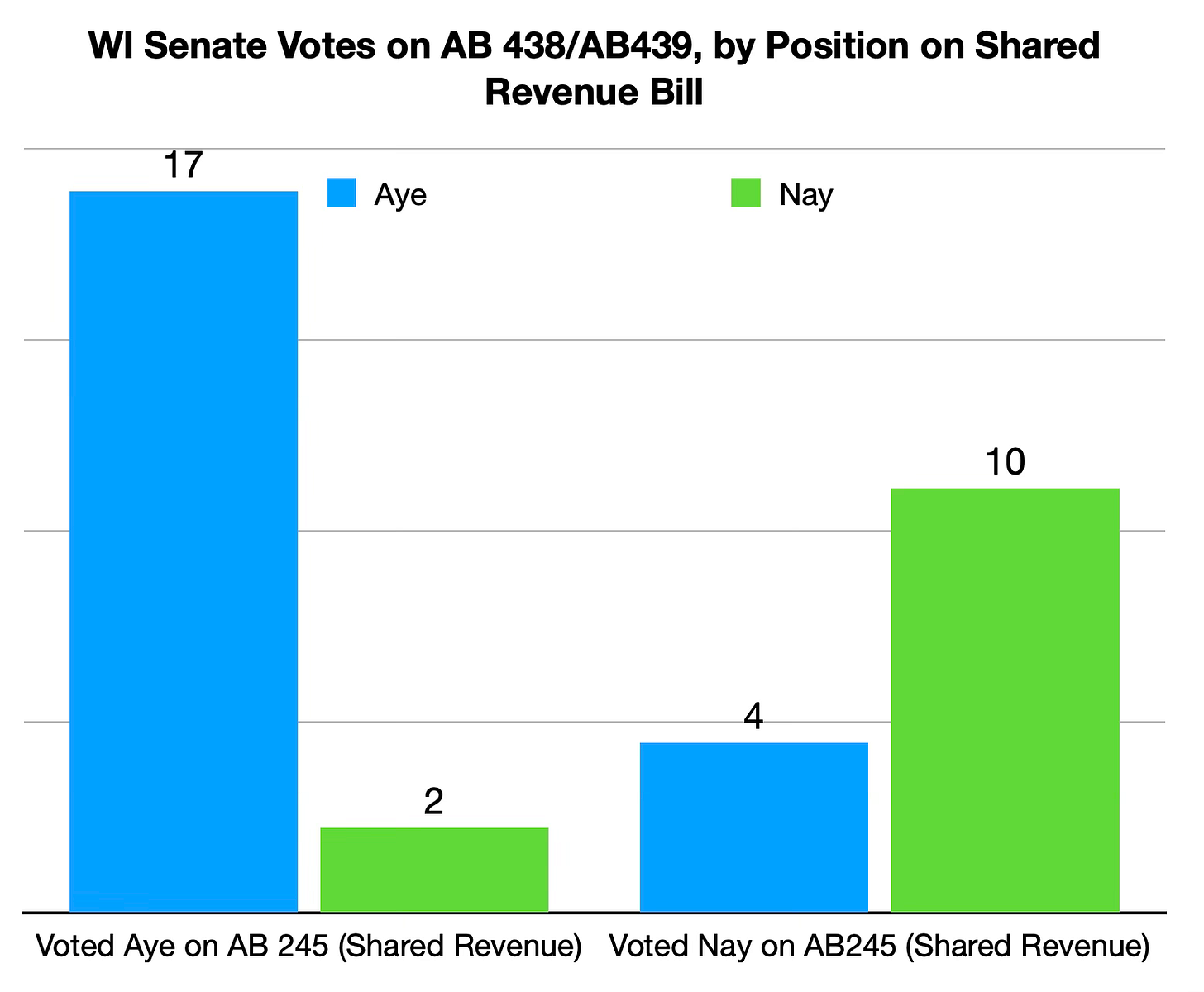

Third, I included a variable indicating whether senators had voted in favor of the passage of Assembly Bill 245, the shared revenue package which became Act 12. My hunch here: a vote for shared revenue would likely be a vote for the stadium deal. Why? If nothing else, covering the (often torturous) journey of that legislation illustrated to me several underlying features of Wisconsin politics that also appear to be present on the stadium financing issue.

Of course, viewed in terms of their primary beneficiaries, the shared revenue and stadium financing packages are quite different. The former was a decades-in-coming boost in local revenue for counties and municipalities across the state (laced with a potent dose of state control and regulation). The latter is a specialized economic incentive package, whose largest beneficiary — whatever the commissioned studies say — will be a single private entity.

Nevertheless, where politics is concerned, the bills have a great deal in common. Both measures enjoyed support from a Democratic governor and Republican legislative leaders, who could be expected to exert pressure on members of their respective parties expressing their objections to “hold their noses” and vote in the affirmative.

Both packages also had some measure of support from a cross-cutting coalition of interest groups. Perhaps most importantly, the Milwaukee Metropolitan Association of Commerce (MMAC) played a leading role in lobbying for both bills. The shared revenue bill also eventually attracted support from interests with a presence in every legislative district: representatives of counties and municipal governments.

And while the Brewers Baseball Club is arguably the central beneficiary from the stadium package, the legislation enjoyed support from a number of labor unions and business associations (including the Tavern League and the Wisconsin Hotel and Lodging Association) that have members across the state. Once the bill was amended to reduce the administrative fee on county sales and use taxes, the Wisconsin Counties Association became a champion of the package, too. Both packages attracted some opposition, as well, but the organizations lobbying to stop or significantly modify the measures lacked either the political or economic muscle to neutralize a coalition sacrée.

Finally, it bears mentioning that both measures were subjected to short, politically constructed time horizons. As I noted in a piece this summer, an important factor explaining the timing of the shared revenue vote was the prospect of fast-arriving budget crises in the city and county of Milwaukee. The “length of the fuse” on the stadium legislation was, in one sense, dictated by the length of the stadium lease itself. Yet given that there are seven years left on the lease, plenty of time for more than a few rounds of legislative bargaining, the short legislative time horizon is better thought of as a political construction than a binding external condition. Illusory though it was, the high-pressure sales pitch evidently had its intended effect.

In short, the political dynamics that shaped the Senate vote on shared revenue provide us with a reasonably good guide to the politics of the stadium deal. As the cross-tabulation below shows, of the 19 senators voting to support the shared revenue package, all but two voted in favor of the stadium deal. By contrast, of the 14 senators voting against the shared revenue deal, all but four opposed the Brewers package.

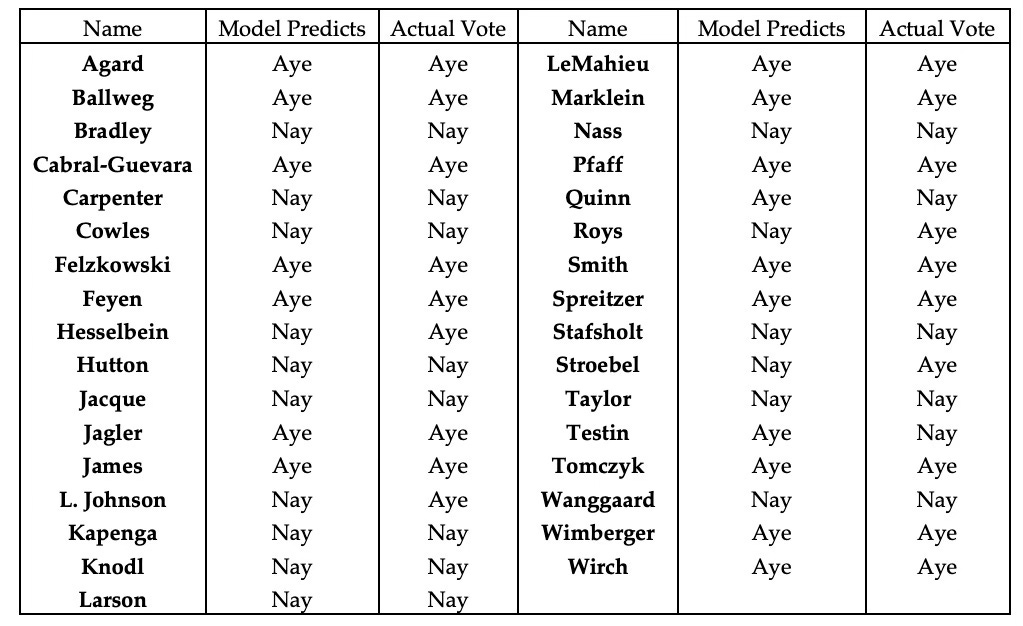

How well does this model of the stadium vote perform, overall? In short: not bad. Without getting into the weeds, it correctly predicts 27 of 33 votes on both bills.

Four of the six errors were incorrect predictions of opposition to the package. Because of their votes against shared revenue, the model predicts that Sens. Kelda Roys (D-Madison) and Diane Hesselbein (D-Middleton) would have opposed the stadium package. But Hesselbein voted for it in committee and Roys flipped to support it on the Senate floor. Similarly, due to the influence of the geography variable, the model incorrectly predicts the votes of Sens. LaTonya Johnson (D–Milwaukee) and Duey Stroebel (R–Saukville).

The errors are perhaps understandable given that the stadium conflict was defined by strong pressure in favor of passage by the leaders of both parties, as well as key economic actors across the state. Another potential explanation for the outcome here, as I have noted elsewhere, is what cognitive scientists call “anchoring effects.” For legislators eager to “get to yes,” even modest changes contained in the final legislation, such as a ticket tax on non-Brewers events, could have felt like a win — even if the final package represented a far higher level of public financing and far fewer guarantees of community benefits than they might have preferred. This is a bargaining technique that has worked for sports franchises for decades. And Wisconsin is, if it wasn’t already obvious, no exception to the rule.

Yet these votes have broader implications for how we understand Wisconsin politics, too. Under a divided government, it might be tempting to think that partisan gridlock is the likeliest outcome. What the evidence here suggests, by contrast, is that when a concentrated set of economic beneficiaries are mobilized, and when the costs of public investment are opaque and diffuse, major changes in the allocation of the public fisc are possible.

But bipartisan legislation doesn’t always lead to the nirvana of good government. In this case, it redounds to the glory of one of America’s oldest and most powerful economic cartels.

Phil Rocco is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Marquette University, and a regular contributor at The Recombobulation Area.

He is the author of Obamacare Wars: Federalism, State Politics and the Affordable Care Act (University Press of Kansas, 2016) and editor of American Political Development and the Trump Presidency (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020).

Subscribe to The Recombobulation newsletter here and follow us on Facebook and Instagram at @therecombobulationarea.

Already subscribe? Get a gift subscription for a friend!

Follow Dan Shafer on Twitter at @DanRShafer.