Time vs. Money: Why the shared revenue deal happened when it did, what it says about Wisconsin's democracy, and what's next

ESSAY from Marquette professor Phil Rocco.

The Recombobulation Area is a ten-time Milwaukee Press Club award-winning weekly opinion column and online publication written and published by veteran Milwaukee journalist Dan Shafer. Learn more about it here.

This essay is by Phil Rocco, associate professor of political science at Marquette University. Rocco is a regular contributor at The Recombobulation Area, and has written a multi-part series on the shared revenue debate in Wisconsin. Read it all here.

In political life, timing is everything.

A sense of time is a prerequisite, perhaps the prerequisite, political disposition. The most masterful legislators have an intuitive feel not just for how to frame important issues or to build coalitions, but also of when to introduce a key proposal or, equally importantly, when to delay its consideration. Not merely orators or dealmakers, they are conductors of a kind.

Time can also affect politics in ways that supersede the talents of any one person. Much action in the public sphere hinges on deadlines — election dates, fiscal years, and legislative calendars — which force action on legislative priorities that might otherwise be passed over until next year, or be left for dead on the future’s gray and misty shore.

No issue or topic, however obscure, is immune from the cycles of political time. And state governments’ decisions about how to share tax revenue with cities and counties is no exception. The Wisconsin State Legislature’s passage on Wednesday of a bill that would provide the largest infusion of state revenue to local governments in decades — all while significantly weakening local governments’ autonomy — is as much a story about when as it is a story about what.

After all, efforts to revise Wisconsin’s broken approach to shared revenue — and to give local governments access to a broader mix of revenue sources — have been on the agenda of local government organizations for years. Yet despite numerous attempts (the issue was routinely a part of the League of Wisconsin Municipalities’ annual legislative agenda), the issue gained zero traction in the Republican-dominated state legislature for years.

And thus the formula for allocating state revenues to local governments — part of a century-old tradeoff in which the state preempted local tax sources in exchange for turning back a portion of its revenue to counties and municipalities — was subject to neglect for two decades. As inflation grew, the real value of County and Municipal Aid cratered – a textbook case of policy drift. Even Gov. Evers’ incremental requests for increases in his first two biennial budgets — the larger of which was $46 million — were rebuffed in full by the legislature.

On Wednesday, however, years of neglect surrendered to — or rather created the conditions for — a kind of Dairyland realpolitik. On the one hand, the Republican-dominated legislature would allocate $274 million to counties and municipalities – roughly half the size of Evers’ initial request and a quarter of the funds it would take to bring the system in line with its pre-2003 trajectory. The legislation passed Wednesday would also provide the City and County of Milwaukee the option to pursue additional sales taxes of 2% and 0.4% respectively — after decades of being an odd outlier among peer cities.

At the same time, however, Republicans set a heavy price: significant new limits on local governments’ autonomy (including, among other things, a prohibition on local non-binding referenda), and a blizzard of unprecedented restrictions targeted specifically on Milwaukee — which seem likely to tee up litigation in state courts.

Even the sales tax provisions came with a major caveat. Unlike Evers’ original proposal, Milwaukee’s new sales tax will not really function like general revenue at all, since it can only be used for accrued actuarial liabilities (pension debt) and public safety. Milwaukee will also be excluded from receiving the minimum 20% increase in shared revenue that all other communities will receive. This is, in other words, a recipe for future fiscal problems.

As if all that were not enough, in the final week of the negotiations, the broader “deal” grew to include provisions in a completely separate bill that would represent a striking win for the forces of school privatization, a shocking development for a “public education” governor.

In short, it would be wrong to describe the bill as a mere “top-up” to shared revenue. Calling the bill a “local government funding package” is just a bit of journalistic shorthand. It is, instead, a renegotiation of the terms on which the state turns back local revenues to communities, a redefinition of the state’s fiscal regime.

To understand the contours of this deal, why it happened now, and what might happen next, we have to get a firmer grip on political time.

Slow-motion state neglect becomes a fast-moving fiscal crisis

“How did you go bankrupt?,” asks Bill Gorton in The Sun Also Rises. Mike Campbell responds simply: “Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.”

Any number of political processes have just the same quality. A bad policy judgment is made. Its consequences manifest themselves slowly at first. As years go on, it slowly dawns on all parties involved that the decision will eventually birth a crisis. The inevitability, however, does nothing to speed a political solution. Only when the floodwaters have reached the door, and perhaps not even then, does the prospect of relief appear.

The story of the bill that came up on the Senate floor on Wednesday is similar. As noted above, proposals for fixing the state’s broken shared-revenue system have floated around for years. What brought things to a head in 2023 was arguably the onset of a fiscal crisis in Milwaukee in the form of a $156 million budget gap that would manifest in 2024. (The County, for what it's worth, has similar fiscal problems — by 2025, for example, its economically critical bus system will face a budget gap of $26 million).

One could clock the oncoming approach of this calamity by looking at the increasingly dire titles of reports published by the Wisconsin Policy Forum documenting fiscal conditions in the state’s largest city: Between a Rock and a Hard Place (2009), Making Ends Meet (2016), and finally – most ominously – Nearing the Brink (2022).

The state government is at the root of these problems. Counties and municipalities are not, contrary to popular myth, masters of their own fiscal fates. The state sets the terms of their fiscal arrangements. It decides what they can tax, sets the parameters of how much they can tax, imposes unfunded mandates that affect their expenditures, decides whether or not their employees are included in the state’s pension system, and — of course — determines the share of revenue it returns to them in exchange.

In Milwaukee, the state’s decisions — ranging from the shared-revenue stasis to the imposition of levy limits — were acutely felt. As the Wisconsin Policy Forum noted last year: “Between 2011 and 2021, the city’s financial statements show revenues grew by only 12.8% in the city’s tax-supported governmental funds, substantially less than the 20.5% increase in the Consumer Price Index during that period.” The only reason the city did not experience pain sooner was the infusion of nearly $400 million in American Rescue Plan Act funds.

By late 2022, a full-blown fiscal crisis seemed unavoidable. Yet this crisis, occasioned by the state’s neglect, spurred Milwaukee’s top political and business leaders to build a proto-coalition to pitch state leaders on a new fiscal deal for the city. If anything, the rest of the package — and the concerns of municipalities and counties around the state — was hitched to Milwaukee’s wagon.

These initiating conditions had, in the end, deeply ironic political effects. While communities around the state depended on energy from Milwaukee to get a boost in shared revenue, Milwaukee’s position at the center of the debate also gave way to a “Milwaukee versus everyone” framing to the debate that invited criticism from the political right – whose talk-show hosts described the bill as a Milwaukee “bailout.”

These ascriptions took their legislative form in a number of (quite likely unconstitutional) Milwaukee-only handcuffs in the legislation: a new rule requiring a two-thirds vote on all new spending in the county and the city, a ban on tax-levy expenditures on the streetcar, the evisceration of civilian oversight of Milwaukee’s police department.

Nevertheless, the inescapable fact is that a looming disaster caused by the state created leverage for state officials to claim credit for getting a deal done. The real question was who would be able to use that leverage. To understand that, we have to examine another critical mechanism of political time: the election cycle.

A legislative election cycle disrupted by gerrymandering

In theory, election cycles — and the prospect of a governing party being thrown out of office — provide a routine way for representative democracies to solve crises. Yet it goes without saying that Wisconsin’s gerrymandered state legislature has essentially disrupted the functioning of the normal election cycle — with significant consequences for the operation of representative democracy. This is not just a problem where shared revenue is concerned. Witness the array of policy proposals – ranging from Medicaid expansion to marijuana legalization to paid family leave – that have been adopted by Wisconsin’s neighboring states, enjoy the support of majorities of Badger State voters, and yet are dead on arrival (as Speaker Vos routinely reminds us) in the state legislature. By removing the threat that the current state legislative majority will ever lose their grip on the state house, gerrymandering undercuts the role of election cycles as mechanisms for policy change.

It is easy enough to see how this happened. In the years that preceded the adoption of Wisconsin’s worst-in-the-nation 2011 gerrymander, close to a quarter of the races for State Assembly seats were competitive. Over the next five election cycles — the very period where Wisconsin communities began to feel the pinch of flat shared-revenue payments — the number of competitive seats was cut in half. By the time that Milwaukee’s fiscal conditions began to reach a crisis point, the state had adopted new, even-more-gerrymandered legislative maps.

And while there is no precise way of quantifying it, any discussion of the effects of gerrymandering must be qualified with a description of the state GOP’s uniquely vindictive approach to wielding power — a brand of arbitrariness that reaches its apex in Assembly Speaker Robin Vos’s petty insistence, following the passage of his chamber’s version of the bill (and to the surprise of his counterparts in the Senate), that he was “done negotiating.” Republicans, of course, could have solved the shared revenue problem or the Milwaukee revenue problem last session. But then again, it was in advance of a gubernatorial election year – no time to allow Evers to claim anything that could be described as a win.

Thus the election cycles that had played the most important role in returning revenue sharing to the state’s policy agenda were not for state legislative seats. They occurred instead at the local and the federal level. By the Spring of 2022, Milwaukee had elected both its first Black mayor, Cavalier Johnson, and its first Black County Executive, David Crowley. These elections contained the potential for a “reset” in the often-contentious relationship between the state and its largest metropolitan units of government. During his election campaign, Johnson routinely made mention of preparing a “cot in the Capitol” – a metaphor signaling his eagerness to work with the state’s Republican leaders to rehab the city’s untenable fiscal arrangements. Yet the state GOP hardly seemed interested in getting to work quickly on helping Milwaukee avoid a fiscal calamity, or simply restoring the old shared revenue formula simply because local officials around the state, from both parties, had long called for it.

Milwaukee nevertheless still had something Republicans wanted. The city — nestled in a swing state — could serve as a stage for Republicans’ 2024 Convention. It had, in any event, most of the necessary amenities: a glistening basketball arena, upscale restaurants and hotels, and even a shiny new streetcar (nevermind that the legislation would prevent Milwaukee from allocating a single levy dollar to this conveyance), and the infrastructure for hosting such a convention was established in 2020, when the city was set to play host to the DNC, before the pandemic scuttled those plans. It was thus Republicans’ prospects in the 2024 presidential election — and not races for state office — that really set things in motion.

By the summer of 2022, Milwaukee’s city government had signed on to host the convention. The train, so to speak, was on the tracks. Yet with the state legislative election cycle so broken by gerrymandering, those tracks still pointed primarily in Republicans’ direction.

The politics of plenary time

Making law is, if nothing else, the art of manipulating time.

On its face, legislative timekeeping seems like a mundane matter — the province of daybooks and Microsoft Outlook. Technically, the Wisconsin legislature operates in a biennial session that begins in January of an odd-numbered year and ends in January of the next odd-numbered year. Legislative business typically takes place during scheduled “floor periods” as well as during sessions either special (called by the governor) or extraordinary (called by the legislature). In an odd-numbered year at the beginning of a session, the legislative clock is also set by the state’s budgeting process, which is designed to conclude on the last day of the fiscal biennium — June 30.

In practice, however, legislative time is an essential political tool, and one that has invited significant controversy in Wisconsin. Witness the legislature’s calling of an “extraordinary session” to strip power from the executive branch following Tony Evers’ victory in the 2018 elections, and the battle in the courts that ensued. Consider, too, Evers’ unsuccessful attempts to call the legislature into special session to deal with issues like gun violence or abortion rights – which invite a “gavel in, gavel out” maneuver from legislative leaders lasting less than a minute. Under Republican leadership, the legislature also typically takes a nine-month break in every even-numbered year, when all 99 Assembly seats and half of the 33 Senate seats are up for re-election.

In the case of the shared-revenue deal, the absence of time was on Republicans’ side in several ways. First, as mentioned above, there was the matter of Milwaukee’s oncoming budget gap. With the local budgeting cycle about to begin, Republican leaders used this short fuse to their advantage — threatening to strip Milwaukee sales-tax options from the measure if Evers did not sign on to the measure by the end of the first week of June. A day later, Evers issued a press release announcing not only his agreement to the deal, which – among other things – maintained restrictions on Milwaukee while giving the city a boost to shared revenue that was half the size of the new 20% floor it created for every other municipality in the state, but paved the way for Milwaukee to raise its sales tax without requiring a public referendum.

At the same time, and to the surprise of many in his party, Evers’ press release announced that the deal also involved major changes in K-12 education policy that could be found nowhere in the shared-revenue bill. In fact, a hearing on this separate legislation (SB330) would not be held until two days before the debate and final votes on the measure. This was significant because, among other things, that bill represented a windfall in spending on a set of institutions that have been a redout of the conservative movement in Wisconsin: voucher schools.

This tight legislative turnaround — two days from first hearing to final passage — was reminiscent of the Assembly’s process on shared revenue, in which a significant amendment with over 90 legislative changes was released to members mere hours before the final vote. Given that the two pieces of legislation were stacked with numerous restrictions, preemptions, and complex distribution formulas, there was little time for public analysis or airing. News coverage of the measures was — even at its best — was thus telegraphic at best. Even some members appeared to be confused about the meaning of some key provisions. All of this was designed to speed things to passage with a minimum of amendments, or even serious questioning.

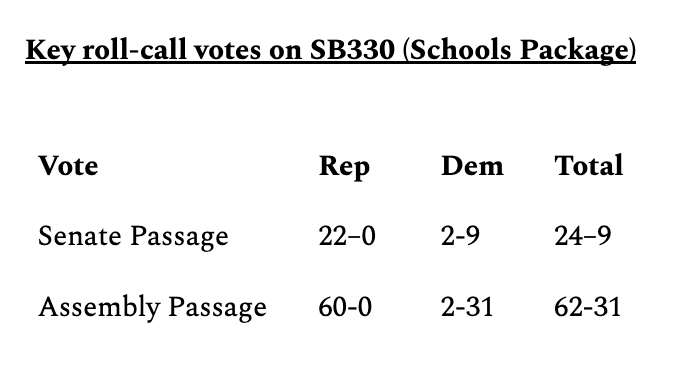

And so it did. As the table below shows, Democrats exhibited far more unity in their opposition to the proposal prior to final passage, during the Assembly’s chaotic May 17 floor session, and in votes to support amendments to the legislation in the Senate, which would have stripped out the onerous Milwaukee-only punishments and increasing funding to medium-sized cities like Janesville, which the Republican formula shortchanged. Yet Republicans quickly called for votes rejecting these amendments, which passed along party lines.

With the promise of amendment eclipsed, Democrats’ united opposition fizzled. In the Senate – where the “Milwaukee bailout” framing still pervaded among some conservative members – five Democrats provided the pivotal votes in favor of final passage.

When it came to the schools package (SB330), Democrats remained more united in their opposition to the measure. But this ended up not mattering on the floor. Republicans — for their part — were far more united in their support of that measure than they had been for shared revenue.

This last move — hitching a shared-revenue bill in the eleventh hour to a change that would divert a historic sum of public money to a parallel school system that has minimal state oversight — is further proof that Republicans did not so much run down the clock as they operated the scoreboard.

The end has no end

Towards the end of the Senate’s debate on the shared-revenue package, Mark Spreitzer — who ultimately voted for it after his amendments failed — issued a warning to his colleagues.

“If you think by passing this bill today, you're not going to have to talk about shared revenue for another decade or more, you're wrong,” Spreitzer said. Democrats, he warned, would “keep talking” about the attacks on local control in the bill and the unfair distribution of aid for cities like Janesville and “we’re going to keep working to repeal them.”

Exactly what that warning meant to Senate Majority Leader Devin LeMahieu is anyone’s guess. Soon after Spreitzer had introduced an amendment to the legislation that aimed to boost funding for medium-sized cities, LeMahieu quipped: "My city's pretty happy with their 20%, so therefore I move rejection." Within a few minutes, the amendment was dead.

In any case, a future reform to the state’s shared revenue system awaits an end to what remains one of the strongest gerrymanders in legislative history. With a shift in power on the Supreme Court, Spreitzer suggested, that day could come as soon as the next election cycle.

Yet a new day in court won’t be enough, either. The planning and organizing capacity for Democrats to be able to take advantage of that opportunity will need to commence long before any case is docketed. What the shared revenue debate has illustrated, if anything, is that Democrats require a more deliberate approach to building inter-regional solidarity. Otherwise, it will remain easy to divide and conquer with policy proposals that single out Milwaukee for special punishments as a kind of political theater.

At the same time, a change to some of the legislation’s strongest challenges to local autonomy — including prohibitions on advisory referenda and especially those applying only to the City of Milwaukee — could arrive even sooner.

As State Sen. Lena Taylor suggested in her remarks on Wednesday: “Maybe [Milwaukee] needs to think about using the third branch for the inequitable way that they've been treated.” There are, indeed, serious questions about whether the Milwaukee-only provisions are even legal under Article IX, Section 3 of the State Constitution – which provides for home rule in municipalities. In several decisions made over the last decade, conservative majorities on the Wisconsin Supreme Court have reconstructed that amendment to the point of meaninglessness, undoing a substantial body of law in the process. If anything, the change in the balance of power on the court creates the potential – the result of another election cycle that mattered — creates the possibility for reversing the assault on local autonomy. The question is whether local officials — particularly those in Milwaukee City Attorney’s Office, as well as organizations like the League of Wisconsin Municipalities — will seize the moment.

This isn’t the last battle on shared revenue. Nor is it the final stage of the fight over local autonomy, or for that matter over the privatization of schools in Wisconsin. But what happens next on any of these issues will hinge critically on whether local officials and key constituency groups who are often disparate, fragmented, and isolated from one another can forge broad coalitions outside of the election cycle to chart a new course for the state. This will require a deliberate effort to shape political consciousness, and resistance to the temptation to treat this bill as “the best that could be done” as opposed to a reflection of a defunct democracy.

The payoffs from these organizing efforts may not emerge immediately. Yet if the time-horizon of the fight seems like a long one, it’s worth remembering that what is at stake is not just the fate of a single bill, but the contours of democracy in the Upper Midwest.

Time to buy a multi-year planner.

Phil Rocco is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Marquette University, and a regular contributor at The Recombobulation Area.

He is the author of Obamacare Wars: Federalism, State Politics and the Affordable Care Act (University Press of Kansas, 2016) and editor of American Political Development and the Trump Presidency (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020).

Subscribe to The Recombobulation newsletter here and follow us on Facebook and Instagram at @therecombobulationarea.

Already subscribe? Get a gift subscription for a friend!

Follow Dan Shafer on Twitter at @DanRShafer.

Thanks, Phil, for your excellent analysis as always. Here in Kenosha, the coalition building is well underway, with full engagement at City Council, County board and school board (its a unified school district) meetings to see how the budget will ultimately unfold. The multi-year planner is on-order.