The Wisconsin State Assembly passed a shared revenue bill. Where does the money go?

And how does it compare to Gov. Evers’ proposal?

The Recombobulation Area is a six-time TEN-TIME Milwaukee Press Club award-winning weekly opinion column and online publication written and published by veteran Milwaukee journalist Dan Shafer. Learn more about it here.

This is a guest column by Phil Rocco, associate professor of political science at Marquette University. Rocco has been a regular contributor at The Recombobulation Area.

Today is the fifth installment in The Recombobulation Area’s coverage of the legislative battle over fixing Wisconsin’s broken shared revenue system — a lifeline that supports critical services provided by counties and municipalities around the state, ranging from fire and police to libraries, parks, and transportation systems.

If you missed any of that, you can read it free here.

Today’s post examines how the aid contained in the Republican-authored plan that passed the State Assembly would be distributed across the state.

Recapping the floor session

Yesterday, I outlined the broad features of the shared-revenue plan (AB245) passed by the State Assembly on Wednesday evening. As I mentioned, the version of AB245 that passed the few significant changes from the original GOP plan.

While the last-minute changes added brought the total amount of county and municipal aid in the Republican plan up to $311 million, that is still just over half the size of the aid package proposed by Gov. Tony Evers. Moreover, while Republicans deleted several “strings attached” to the aid that attracted public scorn — notably the illegal quotas on arrests and moving violations that were part of the plan’s “maintenance of effort” requirements — the vast majority of the restrictions in the initial legislation remained in place.

Arguably the most significant news to emerge from the floor session on Wednesday, however, was the dust-up between Assembly Speaker Robin Vos and Senate Majority Leader Devin LeMahieu — both Republicans — over provisions related to Milwaukee’s sales tax. In recent weeks, one of the most significant concerns raised by the Milwaukee-based coalition advocating for new local sales taxes is that the Assembly legislation requires public referenda for approval. Local officials are worried that such a referendum might not pass.

The morning following the bill’s passing, Senate Majority Leader Devin LeMahieu said the State Senate’s version of the bill would not include the same referendum requirements, the AP reported. Vos responded by saying “That could kill the bill.”

Reflecting this disagreement, the State Senate will hold hearings next week on the original shared revenue bill, without the changes that were made by the Assembly prior to passage. The Senate could vote on its own version of the legislation in early June. But given the differences among Republican leaders, as well as between Republicans and Gov. Evers, it is not clear what the final outcome of the legislation will be.

In the meantime, let’s tuck into the legislation Assembly passed on Wednesday night.

State aid allocations to cities, towns, and villages: What changed?

The elements of the shared revenue plan that arguably attracted the most attention on the Assembly floor last Wednesday were the numerous “strings” attached to the aid plan Republicans introduced, which set it apart from the “clean” approach found in Gov. Evers’ proposal. Yet an equally important feature of this plan is how it allocates state aid to counties and municipalities.

As I mentioned yesterday, Republicans’ plan not only delivers a far smaller amount of aid than Evers’ proposal, it continues to use a different formula for delivering that aid.

This can get complicated, especially because aid to counties and municipalities (i.e. cities, towns, and villages) has long been delivered according to two separate formulas. So for now let’s just look at the municipal side. (in a future post, I’ll do the same thing for county aid).

The old criteria for distributing municipal aid —which Evers’ plan would rehabilitate— relied largely on “aidable revenues,” a measure based on local governments’ net revenue effort, their per capita property wealth, and population.

In the initial version of their bill, Assembly Republicans’ formula for municipal aid relies exclusively on population, but assigns a slightly larger multiplier to communities with populations under 5,000. The new legislation doesn’t really change that basic structure. But it adds a specific formula for aid to municipalities with between 30,000 and 50,000 residents.

What are the practical implications of these tweaks?

Milwaukee County

As we did with the initial version of the Republican plan, let’s begin by looking at Milwaukee County. The table below looks at the aid received by each municipality today as well as the percentage increase in municipal aid found in each bill.

The big story here is very similar to the one we found with the original GOP bill. True, under the amended formula, smaller municipalities in the county get a minimum 15% boost in aid as opposed to a minimum of 10%. But even then, the average aid increase under the revised bill is still, on average, four times smaller than what Milwaukee municipalities would get under Evers’ plan.

And, of course, Milwaukee is effectively the only city in the state that gets a revenue boost below 15%.

While the Assembly Republicans who drafted the bill would likely defend this provision by pointing out that Milwaukee is the only municipality in their bill being granted access to the sales tax, it’s worth remembering that Milwaukee is only being given the authority to hold a referendum, whose passage is anything but guaranteed.

Despite being the economic powerhouse of the state, the only guarantee Milwaukee receives is a shared-revenue boost lower in percentage terms than any other city, town, or village in the state.

The Milwaukee Metro

What happens when we zoom out to the eight counties that make up the Milwaukee – Racine – Waukesha Combined Statistical Area? Again, the story here is not much different from the one in the original GOP bill.

The first graph below looks at the average increase in aid for municipalities in each county under each plan. Here we can see that in six of eight counties, municipalities do far better on average under Evers’ plan than they do under the Assembly Republican bill. In Waukesha County, state aid to municipal governments increases by nearly 450% under Evers’ proposal––double the size of the increase under the Republican plan.

Looked at on a per capita basis, the story is much the same:

The State

Now let’s look at how things break down for municipalities across the state.

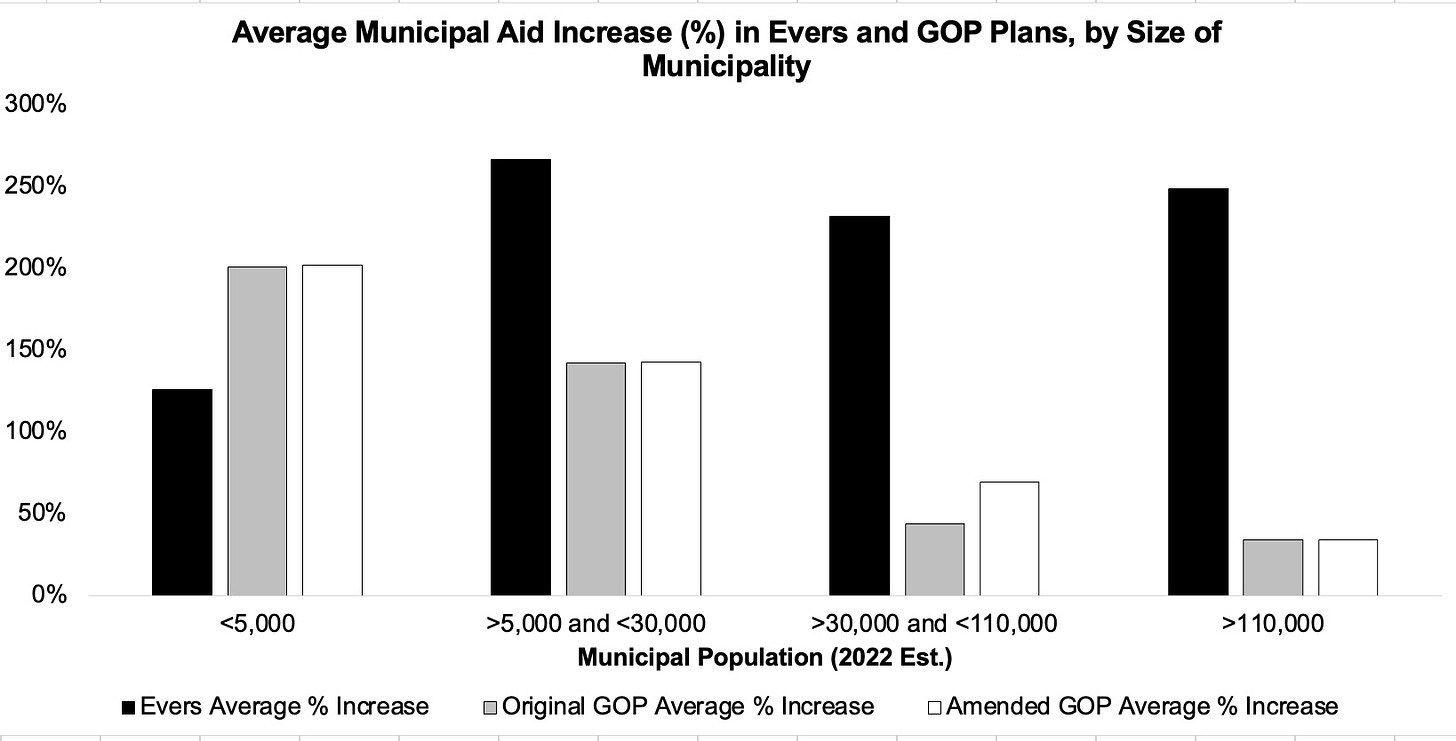

The chart below shows the average increase in municipal aid in the Evers plan (black bar), the original GOP proposal (gray bar), and the version of the legislation that passed on Wednesday night (white bar). It breaks down the data for municipal governments in four population classes ranging from towns with fewer than 5,000 residents to cities with populations that exceed 110,000.

The data here illustrate that municipalities with more than 5,000 residents would still see aid increases far smaller than they would under Evers’ proposal. The disparity between the Evers and the GOP plans is especially dramatic for municipalities with over 30,000 residents. Under the bill passed on Wednesday, municipalities with resident populations between 30,000 and 110,000 would see an aid increase that is still, on average, one-third the size they would receive under Evers’ proposal. For municipalities with resident populations over 110,000, the average aid increase under the bill passed on Wednesday is one-seventh the size of the bump they would see in the Governor’s plan.

The same basic pattern is visible when we look at average per capita municipal aid in the three plans.

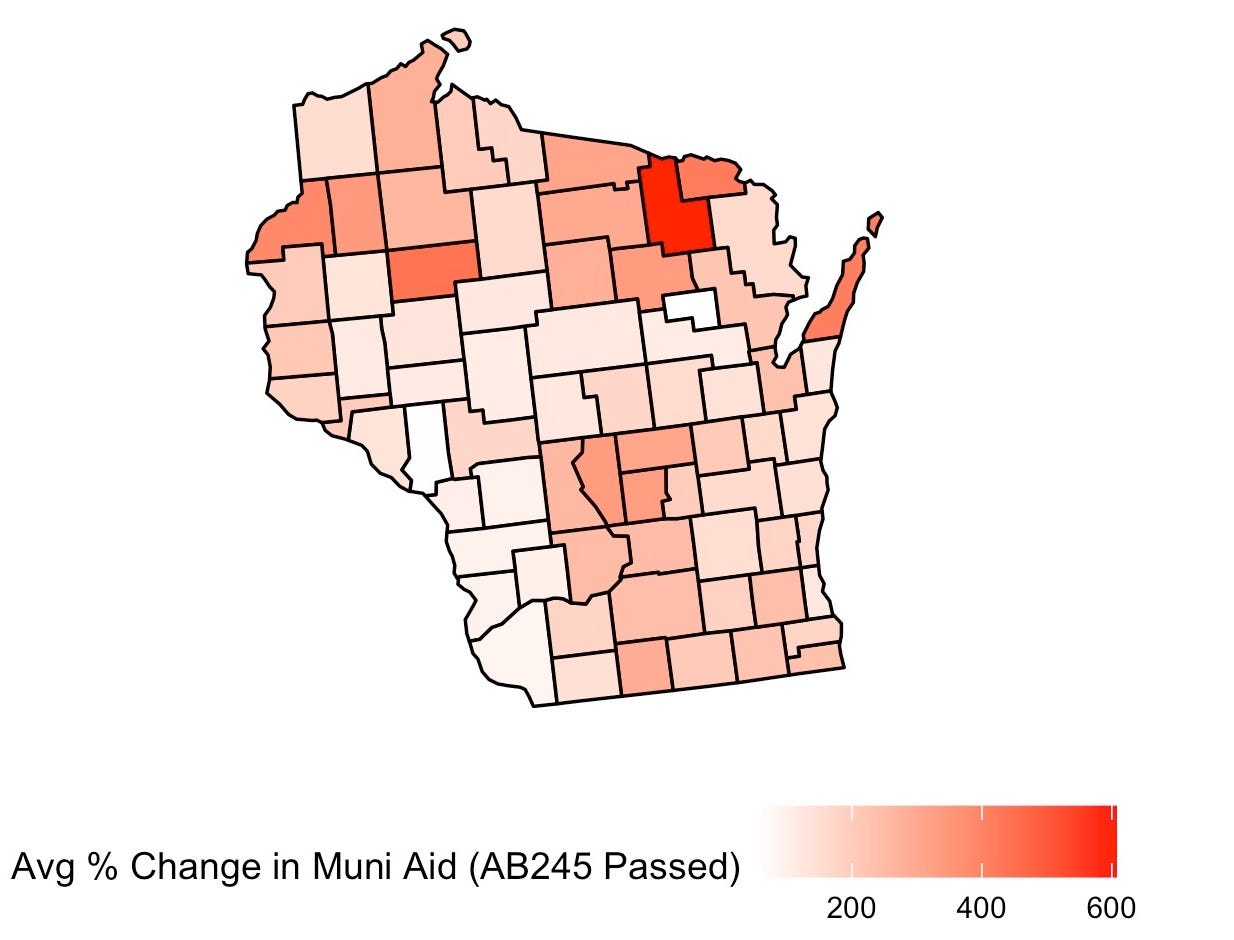

Breaking things down geographically, we also see some stark differences across the three plans. Let’s first look at the Evers plan. The largest average increases can be found in the state’s economic and population centers, which makes sense given that Evers’ plan employs a formula that relies primarily on aidable revenues and population.

The results for both the original Republican plan, and the one that passed on Wednesday night, are substantially similar. In both of these plans, the counties with the largest average increase in municipal aid (Forest, Rusk, and Florence) are all in the far north, and among the most sparsely populated in the state.

Why It Matters

Given the vast differences in how local governments fare under these different proposals, it’s been striking to me to see how little public attention has been directed to the variations in each plan’s formula and the fiscal consequences of these formulas for local governments across the state.

Yes, the formulas are complicated and wonky, but that is precisely why they matter. Their complexity makes them subject to what the late political scientist Richard Nathan once called “politics by printout,” in which the complicated math of revenue sharing is used to conceal how aid is directed to one set of political interests and deprived to others.

In any case, formulas should be evaluated according to whether they meet the purpose of the revenue sharing program itself. Revenue sharing began as a way of compensating local governments for state preemption of local tax sources or the exemption of some forms of property from tax rolls. Formulas with this goal aim to return revenue to its local “origins.”

Yet by the 1970s, a new purpose for state revenue sharing had emerged: tax base equalization. The idea here, as Wisconsin’s Legislative Fiscal Bureau notes, was to “offset variation in taxable property wealth.” Thus between 1976 and 2004, the state’s formula used municipalities’ net revenue effort and their per capita property wealth, along with population, as its key components.

In the debate over shared revenue that’s occurring today, both the details of these formulas and more importantly the point of the county and municipal aid program itself seem to have been lost. This prevents us from asking important questions about whether cities, towns, and villages are getting an appropriate share of aid.

After all, especially given the strings in the plans released by Republicans, what we’re debating here is not just an update to an existing program, but a renegotiation of the terms on which the state shares revenue with municipalities where its residents live.

Phil Rocco is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Marquette University, and a regular contributor at The Recombobulation Area.

He is the author of Obamacare Wars: Federalism, State Politics and the Affordable Care Act (University Press of Kansas, 2016) and editor of American Political Development and the Trump Presidency (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020).

Subscribe to The Recombobulation newsletter here and follow us on Facebook and Instagram at @therecombobulationarea.

Already subscribe? Get a gift subscription for a friend!

Follow Dan Shafer on Twitter at @DanRShafer.

Thank you for this detailed breakdown. I live here and really didn’t understand the machinations of revenue sharing or the differences between each proposal.