There have been many challenges to Wisconsin’s congressional maps. This one is different.

This new "anti-competitive gerrymandering" claim advancing in the courts is not part of the national gerrymandering arms race, nor is it a typical partisan redistricting challenge. So, what is it?

The Recombobulation Area is a 19-time Milwaukee Press Club award-winning opinion column and online publication founded by longtime Milwaukee journalist Dan Shafer. The Recombobulation Area is now part of Civic Media.

One of the biggest political stories of 2025 has been the push for mid-decade gerrymandering of state’s congressional maps.

In June of this year, President Donald Trump encouraged Texas leaders to redistrict the state’s congressional maps mid-decade to give Republicans a greater advantage, and that has kicked off a mid-decade gerrymandering arms race in states across the country.

Most recently, Trump’s pressure to gerrymander was applied to the GOP-controlled state legislature in Indiana, aiming to redistrict a map that produced seven Republican and two Democratic members of Congress to one that would be 9-0 Republican. That effort failed in dramatic fashion on Dec. 11, with a majority of Republican state senators voting against the Trump-encouraged gerrymander, resulting in the current map remaining. Several other states are either in the process of considering a mid-decade redistrict, or have already done so.

So, where does this leave Wisconsin?

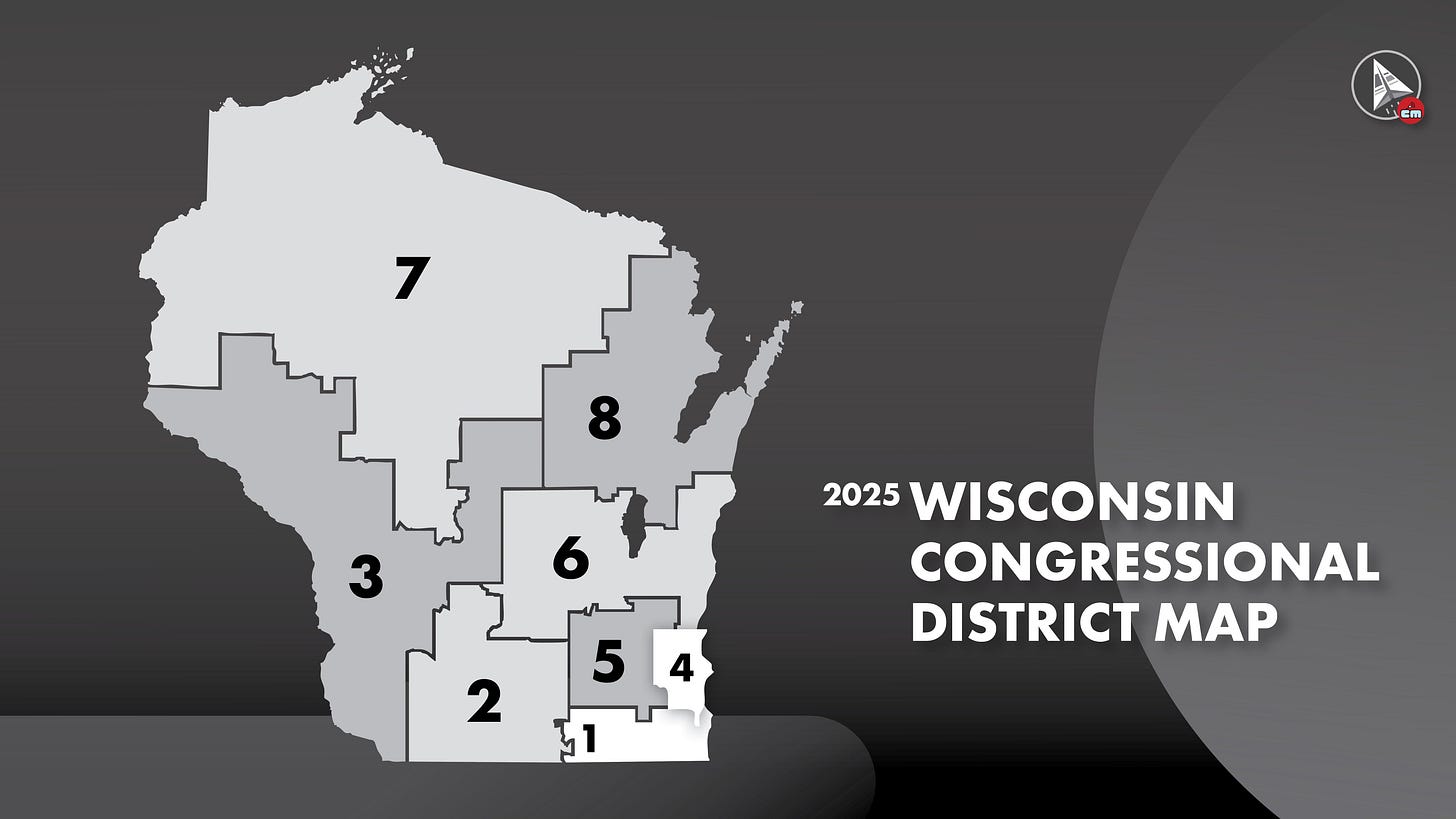

Wisconsin’s congressional district map is not a reflection of what most would consider a “fair map.” While a 50-50 state, Wisconsin’s congressional delegation includes six Republicans and just two Democrats. That breakdown hints at larger problems, even accounting for Wisconsin’s unique political geography. Many have suggested that Wisconsin’s congressional districts indeed constitute a partisan gerrymander.

But Wisconsin has not gone down the path some other states with Democratic governors have in pushing for new maps. Gov. Evers said in September during an interview at CapTimes Idea Fest that “we could not respond to (Texas’ mid-decade redistricting) even if we wanted to” — because it would require cooperation with the Republican-controlled state legislature. The governor added that even if he did have the power to alter the maps to add more Democratic seats, he wouldn’t do it.

“I spent my whole damn life talking about fair maps, and to say, ‘Oh, I’m for fair maps. I want an independent group that develops those fair maps, except when I want to get back at somebody,’ that would be hard for me to do…I couldn’t do it,” Evers said.

In Wisconsin, then, it’s not the governor or legislature central to this latest redistricting discussion. It’s the courts.

The balance of power on the Wisconsin Supreme Court flipped in 2023, following the election of liberal justice Janet Protasiewicz. That opened the door to fresh challenges to the state’s maps. The state legislative maps — widely regarded as among the nation’s worst, warping the state’s politics in a myriad of ways — were struck down on Dec. 22, 2023.

Challenges to the congressional maps haven’t fared similarly. Even after the shift in majority control of the state Supreme Court, justices declined to hear a challenge to the state’s congressional maps brought forth by Elias Law Group. A little over a year later, after now-Justice Susan Crawford was elected to the state Supreme Court, two more challenges — one from Elias, the other from Campaign Legal Center — were also ones the liberal-controlled court declined to hear.

As those suits hit roadblocks, another was developing. Significant news on this matter broke just a few weeks ago, in late November. The Wisconsin Supreme Court said it would be appointing a pair of panels with three Circuit Court judges to hear two lawsuits filed to challenge the maps. One is another partisan gerrymandering challenge from petitioners represented by Elias Law Group, claiming the map “unfairly benefits Republicans.”

The other is from “Wisconsin Business Leaders For Democracy,” represented by Law Forward, the progressive law firm based in Madison that was part of the successful effort to challenge the state legislative maps. Their challenge takes a different, and perhaps more compelling, approach.

“Everybody is so, so focused on the national redistricting fight, and are (asking), how does your case fit into it?” said Doug Poland, co-founder and director of litigation at Law Forward, in an interview with The Recombobulation Area. “I say, well, it really doesn’t.”

In part because this takes a different approach than those rejected previously — filing the lawsuit in Dane County Circuit Court and not going straight to the Wisconsin Supreme Court — a decision on this case is expected to be decided “sometime in 2027,” said Poland.

He added, “Once the (Wisconsin Supreme Court) said they weren’t going to take those original actions, we said, OK, we’re going to do what should be done. We’re going to file our case now in the Circuit Court. We’re going to go through the regular process that other cases would go through.”

This lawsuit claims that the state’s congressional maps are an “anti-competitive gerrymander.”

“Our case is different,” said Poland. “There are really three different kinds of gerrymanders. There’s partisan gerrymandering; everybody pretty much knows what that is now. There’s racial gerrymandering, which is something else that you still can’t do…An anti-competitive gerrymander is a third kind of gerrymander. It’s a more novel claim. It’s a newer claim.”

Added Poland, “Our claim is one that really hasn’t been litigated much before, even in other places, and never in Wisconsin.”

So, what exactly does “anti-competitive gerrymandering” mean?

“An anti-competitive gerrymandering claim is basically party agnostic,” said Poland. “Like a partisan gerrymandering claim, the goal is to put decisions and choices about candidates and who’s going to win back in the hands of the voters. It’s to give them a real choice, but not on a partisan basis. Partisan gerrymandering says either the Republicans or Democrats have squeezed the other party out so they can’t possibly win … Anti-competitive gerrymandering is different. Anti-competitive gerrymandering is one where the districts are so noncompetitive, typically because the two different political parties have sat down and carved up the districts for many different purposes, including protecting incumbents.”

This produces election results that are “so one-sided” where “the margins are so big that these are simply non-competitive districts.”

The concept here with this kind of gerrymander suggests that parties create districts that are especially lopsided — “safe districts” for each party.

“The idea of an anti-competitive gerrymander is if the parties sit down and basically carve up a map in a way that makes safe districts for the political parties, — whether it’s six safe Republican districts and two safe Democratic districts or otherwise — they’re basically killing competition. They’re taking the choices, the decisions away from the voters because the individual votes don’t really matter because the districts are safe. As a Democrat, I might not be harmed because I live in a safe Democratic district. On the other hand, voters generally in that district don’t have a real choice because the parties have conspired to carve up the map that way. So that’s the essence of an anti-competitive gerrymander. You’re really taking away people’s right to be able to have a meaningful choice for who they’re voting for for Congress.”

Of Wisconsin’s eight congressional districts, only the 3rd has been closely competitive since the initial version of these maps were put in place before the 2012 election, with Ron Kind, a Democrat, representing the district until he retired in 2022, and Republican Derrick Van Orden winning that year’s race for the open seat. The 3rd could very well flip again in 2026, as it is expected to be an especially close race. None of the other districts have been closely competitive in any of these elections.

But, as Poland explains, “Just because there is a district that is competitive doesn’t necessarily mean that the map as a whole (is) competitive.”

There’s another element of this worth considering, too, and it goes back to the 2011 redistricting process. At that time, Republicans had just won trifecta control of state government, and while the congressional redistricting process didn’t mirror that of the state legislature — shrouded in closed-door secrecy — it was still highly partisan, and obviously quite tilted.

A decade later, when it was time for the state legislature to “apportion and district anew,” as the Wisconsin State Constitution reads, the court imposed a curious criteria for drawing new maps — “least change.”

This “least change” approach has since been essentially nullified. When the Wisconsin Supreme Court struck down the state legislative maps in December of 2023, it also invalidated the “least change” approach, essentially saying it’s “not a thing,” said Poland. But that has not, as of yet, been applied to congressional districts.

Additionally, said Poland, “The anti-competitive nature of these districts flow out of the court’s previous adoption and application of that ‘least change’ rule.”

The congressional maps eventually adopted in this fraught process in 2021 and 2022 were ones actually submitted by Gov. Evers under the condition of meeting this now-vacated criteria. But under this “least change” approach, that meant the problems with the maps for the 2010s would be essentially baked into the maps for the 2020s.

Though not necessarily the focal point of their challenge, said Poland, “The anti-competitive nature of these districts flow out of the court’s previous adoption and application of that ‘least change’ rule.”

Last Friday, there was a scheduling hearing held on both this case and the Elias Law Group’s partisan gerrymandering case. And over the weekend, on WISN’s UpFront, Jeff Mandell, the other co-founder of Law Forward, said, “The ultimate goal is to have fair maps here in Wisconsin. We do believe that voters are disenfranchised every time we go to the polls without those fair maps, but I don’t know that it’s really realistic to have those for the 2026 elections. And the goal is not any specific election, the goal is fair maps that treat all Wisconsinites well and make sure that everyone’s vote counts and matters.”

As with so many of these redistricting cases, there is an expectation that this will eventually end up in front of the state’s highest court.

“The state Supreme Court is almost certainly going to have the last word here,” said Poland.

Dan Shafer is a journalist from Milwaukee who writes and publishes The Recombobulation Area. In 2024, he became the Political Editor of Civic Media. He’s written for The New York Times, The Daily Beast, Heartland Signal, Belt Magazine, WisPolitics, and Milwaukee Record. He previously worked at Seattle Magazine, Seattle Business Magazine, the Milwaukee Business Journal, Milwaukee Magazine, and BizTimes Milwaukee. He’s won 23 Milwaukee Press Club Excellence in Journalism Awards. He’s on Twitter at @DanRShafer.

Subscribe to The Recombobulation newsletter here and follow us on Facebook and Instagram at @ therecombobulationarea.

Already subscribe? Get a gift subscription for a friend.

Part of a group who might want to subscribe together? Get a group subscription for 30% off!

Follow Dan Shafer on Twitter at @DanRShafer and at BlueSky at @danshafer.bsky.social.

I don’t know how you can say that anticompetitive maps are unconstitutional when you could make a map that’s completely partisan agnostic based on neutral redistricting principles and still get a 6-2 map. As long as you’re not breaking up Madison and Milwaukee into multiple districts, you’re going to have a disproportionate number of the state’s Democrats in just two districts, and those districts will be uncompetitive.

If you’re going to say that partisan maps that favor one side or another violate the First Amendment (or the state constitution’s version of it) because the legislature is putting its thumb on the scales in favor of Republicans, what do you say to a progressive who challenges a map that cracks Madison into two swing districts on the basis that, because Madison isn’t in a solidly blue district any more, progressives are no longer electorally viable? Supporters of a progressive ideology have just as much of a right to not have their voting power diluted by the legislature as Democrats do. If uncompetitiveness is a sign of unfairness and therefore unconstitutional, how would the court evaluate a claim that making districts competitive between the Democrats and Republicans makes them uncompetitive between moderates and progressives?

The other issue is that maps are only uncompetitive if you assume partisan alignments stay the same over time, and that doesn’t always happen. In particular, since the 2011 maps were put in place, Democrats have become significantly weaker in rural areas of the state and significantly stronger in suburban parts. It’s hard to believe now, but the 3rd CD was originally drawn to *pack* Democrats. The idea was that the 3rd and 7th were both swing districts, but if they moved Stevens Point into the 3rd, they could make the 7th redder at the cost of making the 3rd bluer. But the demographic makeup of the parties that make that move make sense aren’t true any more, so now the Democratic pack district is a swing district.