What we talk about when we talk about shared revenue

The stagnation in Wisconsin’s shared revenue program is so significant because the state has historically not given local governments access to the same mix of revenue sources enjoyed by their peers.

The Recombobulation Area is a six-time TEN-TIME Milwaukee Press Club award-winning weekly opinion column and online publication written and published by veteran Milwaukee journalist Dan Shafer. Learn more about it here.

This is a guest column by Phil Rocco, associate professor of political science at Marquette University. Rocco has been a regular contributor at The Recombobulation Area.

On Tuesday, the Wisconsin State Senate held hearings about legislation that would reshape the way the state shares tax revenue with counties and municipal governments.

These hearings (roundups of which can be found here and here) came less than a week after Assembly Republicans passed their version of the legislation.

If nothing else, public testimony on Tuesday demonstrated that municipalities and counties around the state appear desperate to receive any increase in aid, especially in places where fiscal crises loom. As the League of Wisconsin Municipalities’ Jerry Deschane told the committee: “You're going to hear a lot of different ideas about ways we could make this better, or tweak that formula. But the one thing I think I am willing to bet you will not hear today is someone say, ‘Do nothing.’”

That’s true, of course, but the relevant question here is whether the solutions under consideration hit the target, policy-wise. And for many local officials around the state, the legislature’s bills do not.

On Thursday afternoon, the Milwaukee County’s Board of Supervisors approved a resolution calling on the legislature to amend their legislation to increase shared revenue and to ensure “full autonomy” for local governments. The vote on the resolution was 14-2.

One of the major themes that has emerged in my analysis of this legislative fight is that it is about a great deal more than an update to the existing County and Municipal Aid program. More than a mere conflict over the size and scope of local government aid, the aid programs proposed by the Governor and Republican leaders in the legislature represent different positions on the value of local autonomy. As side-by-side comparisons of the legislation have shown, the Republican bills are part of a growing trend of clamping down on local governments’ ability to determine their own fiscal and political structures, what the public administration scholar Chris Goodman calls “nuclear preemption.”

But the aggrandizement of state power in the legislation goes further than is typically recognized in two ways. First, the legislation gives the state control of hundreds of millions of dollars that might otherwise be part of direct county and municipal aid. Second, while making only modest increases in aid to local governments, the Republican proposals allow an unsustainable revenue mix to remain in place at the local level.

Republicans’ $300 million innovation fund: Policy solution or preemption tool?

Let’s consider an aspect of Republican shared revenue legislation that has garnered relatively little attention: the $300 million dollar local “Innovation Fund.” For those keeping score, this fund is larger than the guaranteed aid to counties and municipalities in the original Republican package.

Yet this is not really shared revenue as we know it. Whereas shared revenue payments are guaranteed to counties and municipalities, accessing “Innovation Fund” dollars would not be so simple. Local governments must apply to the state Department of Revenue to receive a slice of this aid in exchange for preparing plans to outsource public services to a private entity or transfer them to another unit of government. To be approved, however, these plans must realize a projected savings of at least 10% of the total cost of providing the service. The bill also does not provide the Department of Revenue with aid or staff positions to administer the fund.

The idea of using state aid to induce cost-saving local government innovations has a long history in Wisconsin, stretching back to Gov. Tommy Thompson’s Blue-Ribbon Commission on State-Local Partnerships. Yet one obvious question here is whether governments proposing such “Innovation Fund” projects could credibly claim cost savings of 10%, the minimum required to receive the aid. The answer? Don’t bet on it.

Where privatization is concerned, a recent meta-analysis of 46 studies found no evidence that private service delivery of waste removal and water services is cheaper than public production. One reason for this, the authors note, is that “many public services are natural monopolies with high asset specificity, as in the case of water distribution, and private production in these cases is unlikely to yield cost savings.” Other recent studies of privatization suggest that even when cost savings does accrue, it often adds up to less than 1%, far below than the benchmark laid down in the most recent versions of both the Senate and Assembly bills .

Additionally, much research on the benefits of privatization ignores the effects of outsourcing on the quality of public services. This is important because the draft statute does not require governments’ applying for innovation funds to demonstrate that they will be able to reduce spending by 10% while maintaining the quality of local services. Especially given the disastrous history of water-service privatization in cities like Flint and Pittsburgh, the absence of any such quality criterion is cause for alarm.

What about the potential cost-saving effects of municipal service consolidation? Here, the evidence is a bit more optimistic, but it’s a bit more complicated than envisioned in the legislation. As one recent study from Cornell University on local service sharing from the state of New York shows, inter-local collaboration produced cost savings in some areas (e.g. sewer, and roads and highways) but not others (e.g. elder services, planning and zoning). In at least one area, solid-waste management, communities that shared services initially generated cost savings, but costs eventually converged with those of governments that did not share services. In no case did the cost savings appear to be anywhere close to the 10% requirement found in the current Republican legislation. The authors of the study conclude that “because the cost savings from service sharing are limited, policymakers should be cautious in their promotion of shared service reforms.”

As with privatization, any measure designed to achieve cost-efficiencies through consolidation has to take into consideration the effects of these policy changes on service quality. One local example here: the consolidation of fire service in Milwaukee’s seven North Shore municipalities in the mid-1990s evidently reduced annual costs while maintaining a higher level of service than communities had seen in prior years. Yet for these communities, cost savings alone was not the only criterion for judging the value of consolidation. Rather, the point of consolidation was to make gains in effective service delivery, too. This is not captured by the crude 10% cost-saving standard in the current version of the Republican legislation.

Inadequate shared revenue isn’t the only problem local governments face.

As the hearings on Tuesday demonstrated, municipalities and counties around the state appear desperate to receive any increase in aid, especially in places where fiscal crises loom. Anissa Welch, mayor of the City of Milton (pop. 5,708) summed it up in a powerful bit of testimony. As Welch put it, despite steady economic growth, and despite numerous actions by her city to support sound fiscal policies, inadequate state aid continues to be a drag on Milton’s progress:

We can barely keep up with the interest that is never ending in partnering with our city. And yet, the funding we have received from the State has actually decreased annually over the past five years. General Transportation aid has decreased to 2015 levels. We had to implement a wheel tax to maintain our roads and support the growth our city is experiencing.

It’s not just a Milwaukee problem, as much as that’s been the focus for much of this debate. It’s a problem for municipalities and counties in every corner of the state.

The fiscal problems local governments currently experience are not simply a function of inadequate shared revenue, however. They are also the result of how the state restricts local government’s ability to collect a balanced mix of revenues.

Another example of this pattern can be found in how Republicans’ legislation treats sales taxes.

First, let’s look at what happens outside the city and county of Milwaukee. Here, Evers’ proposal gives all counties and all municipalities with populations over 30,000 the authority to impose a 0.5% sales tax if approved by local referendum. Neither version of the Republican legislation includes such a provision.

Second, let’s consider Milwaukee itself. Here, the crucial differences between the proposals are not merely how much the city and county can raise, but the purposes to which that new revenue can be allocated. The sales taxes contemplated in both versions of Republicans’ bill can be used only to pay unfunded actuarial accrued liability of the county’s retirement system (i.e. pensions) and for public safety services.

Evers, by contrast, proposes that additional sales tax revenues be used to both “diversify local revenue sources” and to “address unique needs in the state's largest metropolitan area.”

In other words, while the GOP provides less shared revenue in exchange for more restrictions, with the partial exception of Milwaukee, it also largely maintains the status quo for local governments’ own source revenues. This preserves a limited range of revenue options for local governments.

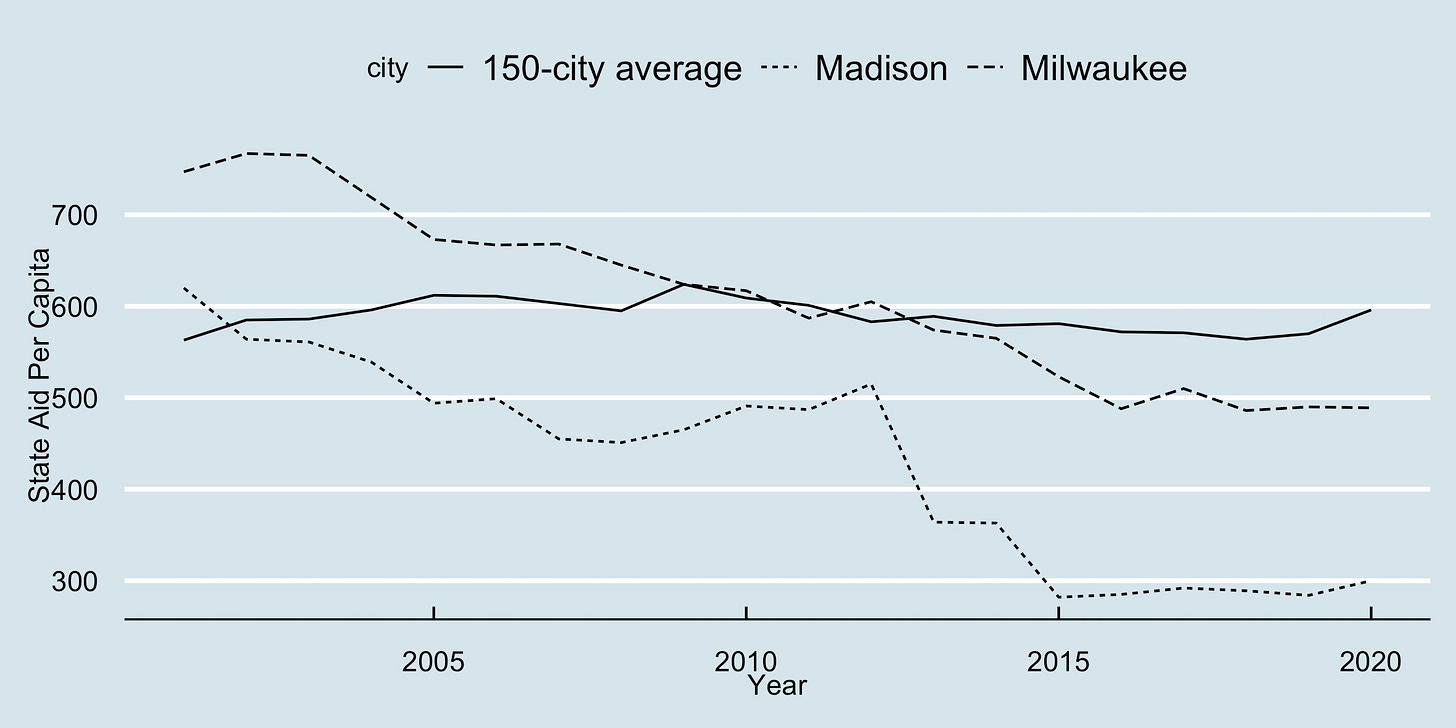

To see why this matters, let’s look at data from a sample of 150 major cities across the U.S., which includes Milwaukee and Madison. As the chart below shows, there’s an inverse relationship between cities’ reliance on state aid as a source of revenue and their ability to collect non-property taxes, including sales, income, and special taxes on other goods or services.

The stagnation in Wisconsin’s shared revenue program is so significant because the state has historically not given local governments access to the same mix of revenue sources enjoyed by their peers in other states.

The chart below compares per capita non-property taxes in Milwaukee and Madison to the average in 150 major U.S. cities between 1977 and 2020 (the figures here are in constant FY2020 dollars). As we can see, over the last four decades, other cities around the country have collected a growing amount of revenue from non-property sources – including but not limited to sales taxes. Madison and Milwaukee have lacked access to these sources of revenue. That’s especially problematic for the City of Milwaukee, where the aggregate value of taxable property per capita is about half the size of Madison’s.

Had Wisconsin's shared-revenue program kept up with inflation, the situation would not be so dire. But it has not. As the chart below shows, over the last two decades, state aid per capita in Milwaukee and Madison has fallen well beneath the 150-city average.

What has been largely missing from the debate is an explicit discussion of the purposes of shared revenue and how it fits into Wisconsin’s broader system of government. What is the rationale for drastically revising the state aid formulas? How well do the bills under the discussion fare when considering important policy goals, such as property tax relief, tax-base equalization, local revenue diversification and growth, and the preservation of local autonomy?

And how does state aid itself compare with other options for reforming state-local relations, including expanding local governments’ revenue mix, and metropolitan tax-base sharing (e.g. the Twin Cities metro area’s Fiscal Disparities Program)?

The state legislature’s failure to seriously consider this issue over the last two decades, a failure which has helped to produce a looming fiscal crisis in cities like Milwaukee, means these important questions might not be answered prior to the passage of shared revenue legislation.

But in the years to come, issues like these — which fundamentally shape who governs Wisconsin and to what ends — will be impossible to avoid.

Phil Rocco is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Marquette University, and a regular contributor at The Recombobulation Area.

He is the author of Obamacare Wars: Federalism, State Politics and the Affordable Care Act (University Press of Kansas, 2016) and editor of American Political Development and the Trump Presidency (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020).

Subscribe to The Recombobulation newsletter here and follow us on Facebook and Instagramat @therecombobulationarea.

Already subscribe? Get a gift subscription for a friend!

Follow Dan Shafer on Twitter at @DanRShafer.

The fight has always been about how to share shared revenue. Back in the halcyon days of Tommy Thompson, the state had an extra billion dollars to distribute. It missed the opportunity to be truly charitable. But the need to move away from the property tax to fund almost everything consumed legalese then, as now. The way the dilemma was resolved was far from ideal -- but this isn’t utopia, its Wisconsin.