More than 90% of Wisconsin counties would see a greater aid increase under Evers’ plan than under Assembly Republicans’ bill

The latest from Phil Rocco's series breaking down the shared revenue overhaul working its way through the Capitol in Madison.

The Recombobulation Area is a six-time TEN-TIME Milwaukee Press Club award-winning weekly opinion column and online publication written and published by veteran Milwaukee journalist Dan Shafer. Learn more about it here.

This is a guest column by Phil Rocco, associate professor of political science at Marquette University. Rocco has been a regular contributor at The Recombobulation Area.

This morning, the Wisconsin State Senate holds its first hearing on a Republican proposal to reshape the state’s system for sharing revenue with local governments. While there is broad bipartisan agreement that something needs to be done to improve the system, there remain a number of important differences in the proposals advanced by Democratic Governor Tony Evers and Republican state legislative leaders. We’ve reported on those differences, which include both the size of the package and the number of restrictions or “strings attached” to new local funding, here and here.

The path to reforming shared revenue is a narrow one, however. Following the passage of the Assembly’s version of the bill last week, another rift opened up between Republican leaders in the State Assembly and the Senate concerning provisions affecting Milwaukee’s ability to levy an additional local sales tax.

Whereas Senate Majority Leader Devin LeMahieu has expressed interest in removing a requirement for new Milwaukee sales taxes to be approved by a public referendum, Assembly Speaker Robin Vos has reported that any attempt to remove that requirement, which he supports, could “kill the bill.”

Whatever the outcome of the Milwaukee sales tax provisions, any Republican-advanced proposal is likely to differ from the governor’s when it comes to how much additional county and municipal aid is provided and how it is allocated.

Last Friday, I wrote about how aid to municipalities would be distributed across the state under the Evers plan, the original Republican proposal, and the amended bill that passed the Assembly on Wednesday. Today, I want to extend that analysis to how these different proposals would support Wisconsin’s 72 county governments.

The big takeaway from this analysis is that all but six of Wisconsin’s 72 counties do better under Evers’ proposal than they do under the amended plan passed by Assembly Republicans last week. And all Wisconsin counties do better under Evers’ plan than they do under the original version of Republicans’ legislation.

This stands in contrast to what we saw with municipalities, where the most sparsely populated saw higher percentage increases in aid than those with larger numbers of residents. Nevertheless, when compared to both the original and amended version of the Republican bill, Evers’ proposal brings counties far closer to where they would be if the old shared revenue formula were updated for inflation.

Putting County aid in context

When compared to cities, counties are often far less visible units of local government. Political scientists often refer to them as “forgotten governments.” Nevertheless, counties impact the quality of life in metropolitan areas in profound ways. This is especially true because counties, while jurisdictions in their own right, are also an administrative branch of the state government, and a provider of crucial public services. As Milwaukee County Executive David Crowley noted in the County’s 2023 budget, over 70 percent of the county’s local tax dollars support state-mandated services. “These state mandates,” Crowley continued, “are growing twice as fast as our ability to pay them.”

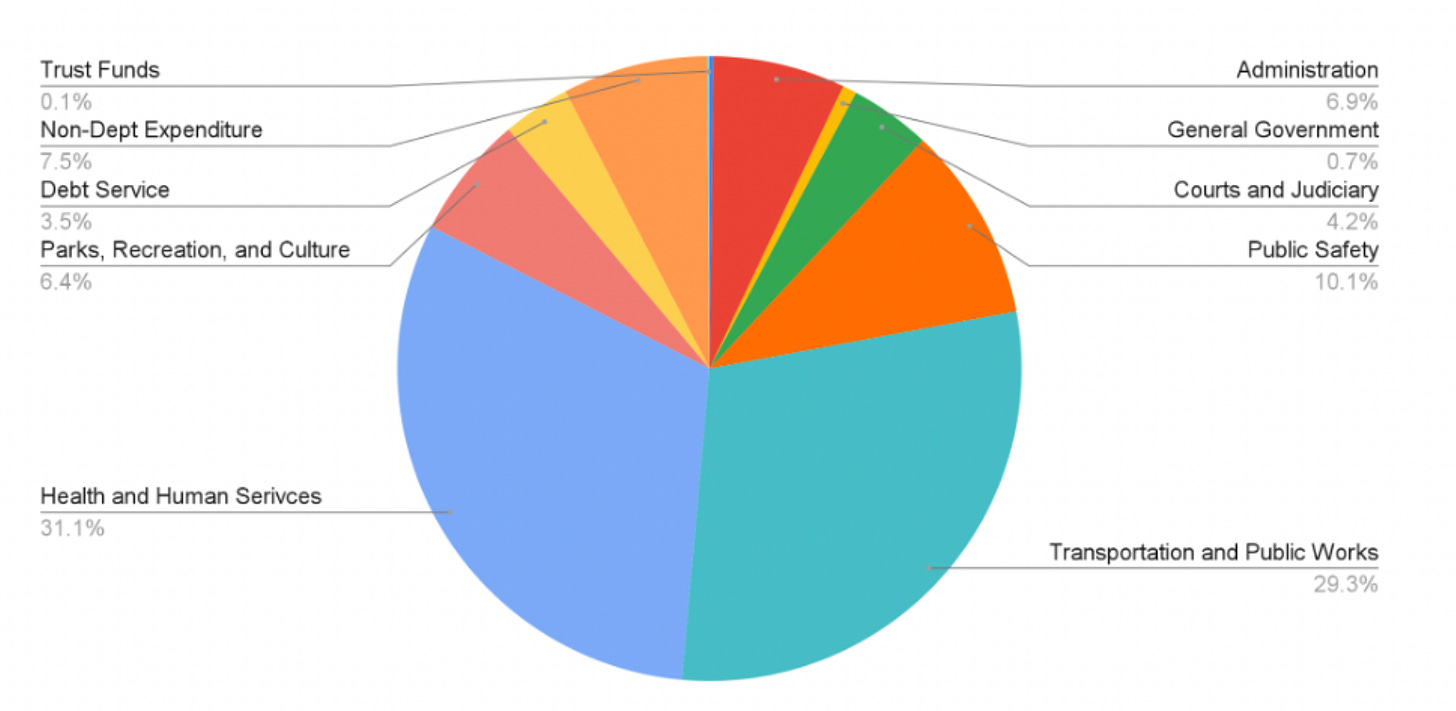

The image below depicts the allocation of expenditures in Milwaukee County’s 2022 budget. As is visible here, the county’s top expenditure item is consistently the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). That covers everything from providing resources to Milwaukee’s aging and disabled populations to inpatient and outpatient behavioral healthcare. Among the programs that the County’s DHHS provides is Housing First, an outreach program that has helped to reduce the County’s homeless population over the last four years (and was honored by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development for helping the county’s unsheltered population reach lowest-in-the-nation levels). The County also manages a right-to-counsel program, Eviction Free MKE, which has helped to slow the pace of evictions since it was first implemented in September 2021.

Transportation and Public Works accounts for more than a quarter of the County’s most recent budget. This involves managing two airports and the system of County Trunk Highways. It also means operating the Milwaukee County Transit System (MCTS), whose buses provide nearly 29 million rides each year. Like public transit systems around the country, MCTS has faced challenges during the pandemic, with staffing shortages causing gaps in service over the last few years.

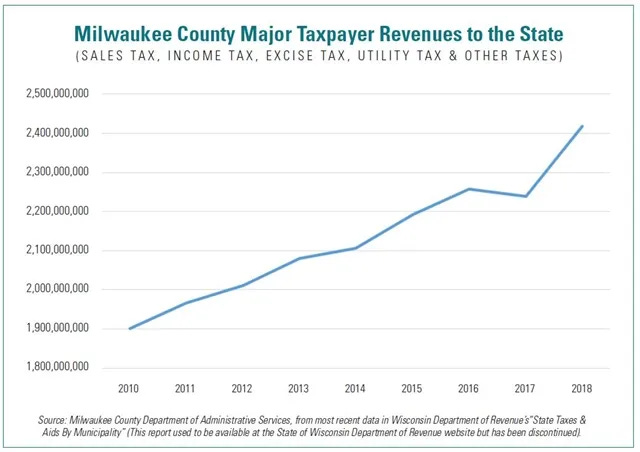

State aid has long been a crucial component of county revenues. Across Wisconsin’s 72 counties, aid from the state funds about 27% of the cost of services. The lion’s share of this aid comes through the state’s shared revenue program. Yet as with municipalities, state aid to counties has remained stagnant in recent decades. As the Wisconsin Policy Forum points out, while state income tax revenue tripled between 1993 and 2021, funding for the state’s shared revenue program remained flat.

Milwaukee County leaders focused on this discrepancy when pitching a sales tax increase in recent years, sharing these charts:

Given this context, the contrast between Evers’ county aid proposal and those found in the Republican bills (both the initial GOP proposal and the version of Assembly Bill 245 that passed last Wednesday) is striking. While county aid represents a small share of aid in both proposals, Evers’ plan would send $272 million additional support to counties, a 122% increase over current levels, and roughly double the amount found in the Republican proposals. As we’ll see, this has some significant consequences for how counties fare under each of the plans.

The Milwaukee Metro

It’s useful to begin our analysis by zooming in on the eight counties that make up the Milwaukee–Racine–Waukesha Combined Statistical Area. The most noticeable trend here is that all of these counties do far better under the Evers proposal than they do under the Republican bills. On average, the Evers plan would yield a 732% increase in county aid across these eight counties – double the size of the increase in the version of AB245 that passed on Wednesday.

What do these changes mean in dollar terms? Under Evers’ plan, the average Milwaukee-area county would receive $36 per capita. That is 150% higher than the average per capita payment under the Assembly-passed version of the plan.

The State

How do Wisconsin’s 72 counties fare under Evers’ plan when compared to the plans advanced by Republicans?

The most basic answer to that question is very simple. Of those 72 counties, 92% – that is, all but six – see a larger share of aid under Evers’ bill than they do under the bill passed by the State Assembly. Those six – Crawford, Lafayette, Menominee, Pepin, Richland, and Shawano – are among the most sparsely populated in the entire state. Relatedly, all counties do better under Evers’ proposal than they do in the original version of the Republican plan.

To further explore these results, I broke down the data here into four classes based on county populations, ranging from counties with fewer than 20,000 residents to counties with more than 100,000 residents. Probably the most striking thing to note here is that, whereas the smallest municipal governments receive a larger bump under the GOP plans, counties of all sizes do better under Evers’ plan than either version of the Republican legislation. Even counties with fewer than 20,000 residents see a 506% increase under the Evers’ proposal, more than double what they would receive under either Republican plan.

When we look at the aid payments in dollar terms, we see that larger counties receive less aid per capita under all three plans. Yet with the exception of the smallest counties, per capita aid payments are higher under the Evers plan than they are under either version of the Assembly Bill.

Putting it all together

Combining the evidence here with the data I presented in my last analysis, the results are striking. All but six counties – and all but the smallest municipalities – do better on average under Evers’ proposal than they do under the Republican bill passed by the Assembly last week. And all counties do better under Evers’ bill than they do under the original GOP legislation.

Moreover, whereas Evers’ proposal represents a more-or-less “clean” approach to reviving the old shared-revenue program, bringing it up to date with current fiscal and population trends, the Republican proposals appear to alter the meaning of the old program, both by introducing additional restrictions on expenditures and retooling the formula to abandon the “aidable revenues” concept and to advantage smaller municipalities. Further, the Republican bill siphons away $300 million from direct county and municipal aid into an application-based “innovation” program centrally administered by the state.

Where advocacy from county officials is concerned, we’re more likely to see pushback on the Republican legislation from individual county leaders. This Thursday, Milwaukee County Board of Supervisors will take up a resolution which authorizes the county’s Office of Government Affairs to push state lawmakers to amend the shared-revenue to include additional aid and greater local autonomy. At the same time, Waukesha County Executive Paul Farrow has criticized the Republican package for amounting to a “bailout” of Milwaukee while providing inadequate support for Waukesha County and including “just enough strings to tie our hands and prevent us from using the funds in the best way possible.”

For its part, the Wisconsin Counties Association has been relatively quiet about the shape of the legislation and has registered as a supporter of both versions of the Republican bills.

By contrast, the League of Wisconsin Municipalities is now pledging to “advocate for an increase in the minimum funding for communities” as well as amendments to the preemption provisions and maintenance-of-effort requirements.

Exactly what changes this advocacy will produce in the shape of the final agreement, if any, remain to be seen.

Phil Rocco is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Marquette University, and a regular contributor at The Recombobulation Area.

He is the author of Obamacare Wars: Federalism, State Politics and the Affordable Care Act (University Press of Kansas, 2016) and editor of American Political Development and the Trump Presidency (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020).

Subscribe to The Recombobulation newsletter here and follow us on Facebook and Instagram at @therecombobulationarea.

Already subscribe? Get a gift subscription for a friend!

Follow Dan Shafer on Twitter at @DanRShafer.