Shared Revenue Reform: Evers’ plan vs. Assembly GOP plan

The Republican bill sends a far smaller amount of money to local governments and has a far greater number of restrictions, mandates, prohibitions, and preemptions.

The Recombobulation Area is a six-time TEN-TIME Milwaukee Press Club award-winning weekly opinion column and online publication written and published by veteran Milwaukee journalist Dan Shafer. Learn more about it here.

This is a guest column by Phil Rocco, associate professor of political science at Marquette University. Rocco has been a regular contributor at The Recombobulation Area.

Today is the second installment in The Recombobulation Area’s coverage of the legislative battle over fixing Wisconsin’s broken shared revenue system.

As I noted in my last piece, this is a gigantic, complicated piece of legislation, with lots of implications for how hundreds of millions of Wisconsin taxpayer dollars get divvied up across the state.

Since I last wrote, Gov. Tony Evers has announced that he will not hesitate to block the Assembly GOP plan. “The state must step up more than what I’ve seen," Evers said. "It’s why I can’t support the Republican plan as is — and frankly, I’ll veto it in its entirety. "

It’s easy enough to see why. While both plans provide some amount of new shared revenue, the similarities end there.

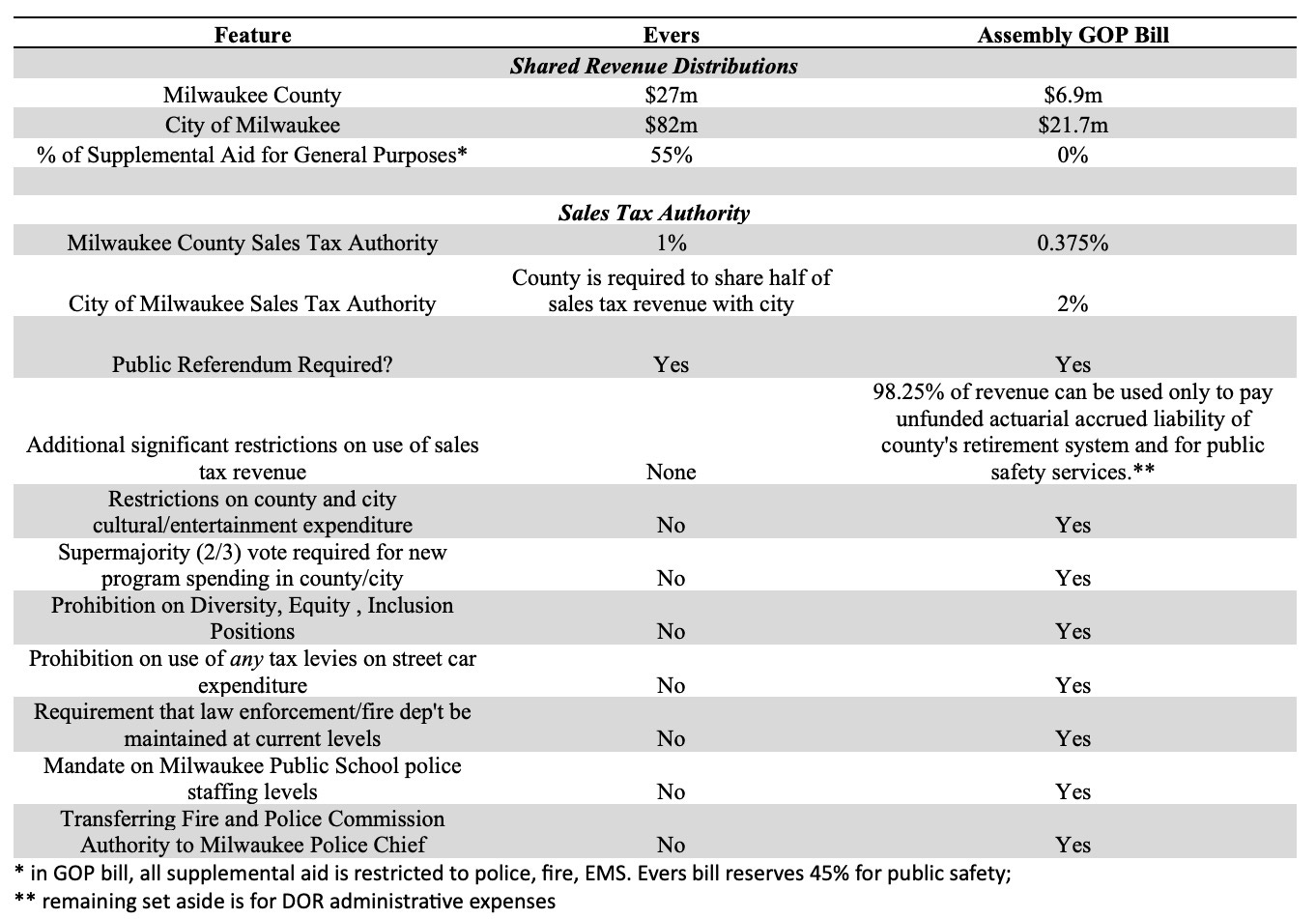

A comparison of the two plans illustrates vast differences—not just in the level of spending they allocate, but how they distribute the aid, and the number of conditions or “strings” they attach to local governments’ ability to receive that aid. Evers has proposed a more or less “clean” revenue sharing bill that distributes $576 million in aid along with a new option for local governments to generate revenue from new sales taxes. By contrast, the Republican bill is not only smaller (about half the size of Evers’ proposal), it introduces a host of new conditions on the aid it provides. Where the City and County of Milwaukee are concerned, the differences between the two pieces of legislation are especially stark.

Here’s a summary of how the major differences between the two bills break down.

1. Size

As noted above, the most obvious difference between the two bills is their size. Whereas Evers’ provides an additional $576 million in shared revenue to cities and counties, the Republican proposal is about half that size. To put that in context, consider that if City of Milwaukee’s shared revenues had kept pace with inflation over the last two decades, it would be receiving $400 million from the state per year rather than the $217 million it receives today. Evers’ proposal would add $82 million to the city’s coffers, whereas the Assembly GOP bill would add only $21.7 million. That’s a huge difference.

2. Who Gets What?

As I noted in my last piece for The Recombobulation Area, another distinguishing feature of the Assembly GOP bill is how it allocates aid. Wisconsin has not had a formula for allocating shared revenues since roughly 2003. Aside from a few changes, municipalities receive the same payment they did in 2012.

What that means is that the ghost of the old formula still lingers, shaping the distribution of aid, but aid amounts are not updated to reflect changes in the formula. Most of the aid under that old formula was allocated according to “aidable revenues”––a measure based on local governments’ net revenue effort and their per capita property wealth. A smaller share was based on the size of the local population. (For more on what this all means, I’d recommend checking out this oldie-but-goodie report from the Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau).

Evers’ legislation largely brings back this arrangement—and thus the principles on which shared revenue has long operated in Wisconsin, which emphasize that shared revenue is not a gift from the state to local governments but a “return” of revenue sources the state has preempted.

The GOP bill changes it to advantage very small communities, with populations of less than 5,000. Under the new formula, these communities are eligible to receive a larger base payment than larger local governments. Moreover, the formula includes a higher population multiplier. This is why, as I explained in my last post, some small communities will see a change in state aid that exceeds 1,000%. By contrast, larger municipalities—like Green Bay, Racine, La Crosse, and Milwaukee – will see only marginal gains over their current level of revenue. (I’ll leave aside for the moment how this shakes out for county governments, except to say that the GOP proposal contains what is surely one of the most complicated aid formulas in American intergovernmental relations––one that is so complicated it cannot be easily represented in a table.)

3. Strings Attached

Another distinguishing feature of the Evers proposal is that it largely maintains local autonomy. Of the $576 million in additional revenue Evers provides, only 45% is functionally restricted to public safety. By contrast, 100% of the new aid in the Republican plan—all of it—is categorical. It can only be spent on Police, Fire, or Emergency Medical Services.

Yet this is not where the GOP bill’s restrictions on local spending end. Among other things, the Assembly bill requires local governments to certify that they are maintaining the level of law enforcement that is at least equivalent to that provided in the previous year or else risk losing 15% of their total municipal aid. As some have pointed out, one of the compliance criteria here amounts to an arrest quota, which is currently illegal under Wisconsin state law. Other restrictions on local governments include a new ban on the use of advisory referenda, restrictions on the power of local public-health officials, and a new preemption of local regulation on…quarries.

Compared to Evers’ relatively “clean” revenue sharing bill, the Assembly proposal is a Christmas tree festooned with handcuffs.

4. Sales Taxes Outside Milwaukee

Another difference between the two bills—and one which has attracted relatively little attention—is how they each treat sales taxes outside of Milwaukee.

Under Evers’ plan, all counties, and all municipalities with populations over 30,000 other than the city of Milwaukee, have the authority to impose a 0.5 percent sales tax if approved by local referendum.

The Assembly GOP bill simply does not allow local governments to take advantage of this new revenue source. And, when it comes to sales taxes in Milwaukee—well, let’s just say that the authors of the Assembly bill are aiming to extract a bit more than a pound of flesh.

5. Treatment of Milwaukee City and County Governments

The way that the two proposals treat the City and County of Milwaukee—the state’s largest metro area—are like a window into their respective souls.

First, there is the matter of shared revenue. As noted above, Evers’ proposal—both because of its size and its formula—is a far better deal for Milwaukee City and County. Under the plan, both governments would collectively see roughly four times the aid they’d see under the GOP legislation.

Second, there is the question of the sales tax. The force behind this has been the public and private sector coalition called “Move Forward MKE” which has pushed for allowing Milwaukee to raise a locally-controlled sales tax by up to 1%. Under Evers’ plan, Milwaukee County voters could—through a referendum—decide to impose an additional 1% sales tax, half of which would be shared with the City of Milwaukee. Beyond that, both governments would have autonomy in deciding how those funds are spent.

Under the GOP, the sales tax would work differently. The City of Milwaukee could—if voters approve it in a referendum—impose an additional 2% sales tax. If a separate countywide referendum passed, Milwaukee County could impose a sales tax of 0.375%. Unlike Evers’ plan, however, those new sales tax revenues could only be spent on paying unfunded actuarial accrued liability of the county’s retirement system and for public safety services.

Yet that is not the only restriction imposed by the GOP bill. In fact, other restrictions in the proposal extend not just to the use of the new sales tax revenues but to local tax revenues, full stop. For example, under the Assembly bill, the City of Milwaukee cannot spend more than 5% of its total budget on cultural or entertainment matters or “partnerships with nonprofit groups.” Second, the city may not use tax levy funds for any position that involves improving the diversity of the local government workforce “on the basis of their race, color, ancestry, national origin, or sexual orientation.” Third, Milwaukee may not use any tax levy money on “developing, operating, or maintaining” its emerging streecar system. Fourth, the Milwaukee Public School District must maintain minimum staffing for a police force (“school resource officers”) in the city’s schools.

If these mandates seem extreme, there are others that cut even deeper into the heart of local autonomy in the Milwaukee area. Under the GOP proposal, city and county governments can only enact new expenditures by a supermajority (2/3rds) vote. This provision would essentially direct governments to abandon the principle of majority rule in local expenditure decisions. It arguably represents one of the most severe incursions of a state government into the traditional sphere of local decision-making anywhere in the United States. Equally importantly, the proposal eliminates the authority of Milwaukee’s civilian-controlled Fire and Police Commission—transferring that power to Milwaukee’s Police Chief, eliminating democratic control over public safety decisions in the state’s largest city.

The Bottom Line

While both the Evers and Assembly GOP proposals represent an “update” to Wisconsin’s shared revenue policies, they depart from one another in every significant respect. Not only does the GOP legislation represent a far smaller resource commitment to local governments, its formula advantages small towns that are largely (though perhaps not exclusively) in the Republican column while shortchanging the state’s largest cities.

Yet the differences here are not just about money—or who gets what from the state—they are also about power. With the exception of the 45% set-aside for public safety, Evers’ legislation is essentially a “clean” revenue sharing bill, with an option for local governments to enact new sales taxes—bringing the state into line with many of its peers.

By contrast, the Republican bill conditions a far smaller amount of money on a far greater number of restrictions, mandates, prohibitions, and preemptions. In exchange for less, local governments across the state must give up more. And where Milwaukee is concerned, local officials must—in exchange for a restricted-purpose sales tax– give up power over some of the most important aspects of budgeting and decision-making.

In short, this legislative fight has significant consequences not just for the fiscal health of Wisconsin’s 72 counties and over 1,800 municipalities, but for the basic structures of local democracy in the Badger State.

Phil Rocco is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Marquette University. He is the author of Obamacare Wars: Federalism, State Politics and the Affordable Care Act (University Press of Kansas, 2016) and editor of American Political Development and the Trump Presidency (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020).

Subscribe to The Recombobulation newsletter here and follow us on Facebook and Instagram at @therecombobulationarea.

Already subscribe? Get a gift subscription for a friend!

Follow Dan Shafer on Twitter at @DanRShafer.