How municipal governments would fare under Assembly Republicans’ and Tony Evers’ shared revenue plans

There are huge differences between the two plans for cities, villages and towns across Wisconsin.

The Recombobulation Area is a six-time TEN-TIME Milwaukee Press Club award-winning weekly opinion column and online publication written and published by veteran Milwaukee journalist Dan Shafer. Learn more about it here.

This is a guest column by Phil Rocco, associate professor of political science at Marquette University. Rocco has been a regular contributor at The Recombobulation Area.

Today is the third installment in The Recombobulation Area’s coverage of the legislative battle over fixing Wisconsin’s broken shared revenue system.

Last Friday, I analyzed the major differences between State Assembly Republicans’ proposed changes to those proposed by Gov. Evers. The bottom line: The plans differ not only on size – Evers’ plan delivers more than twice the total amount of aid – but also on how they envision the relationship between state and local governments.

Assembly Republicans’ bill conditions a far smaller amount of money on a far greater number of restrictions, mandates, prohibitions, and preemptions. By contrast, Evers’ proposal—except for a 45% set-aside for public safety––is a “clean” bill that revives a revenue-sharing system that has been stagnant for the last twenty years.

Today, I want to dive more deeply into another difference between the two bills: how they allocate aid across the state’s more than 1,800 municipalities (Note: I’m going to leave aid to counties aside for the moment and return to them in another post). This kind of analysis not only helps us understand “who gets what” from the various packages, it also allows us to evaluate the extent to which each plan really resembles a meaningful “update” to the shared revenue system itself that address the fiscal conditions local governments face today.

Comparing the Allocation of State Aid

As mentioned last week, Republicans’ package is not only smaller than the one Gov. Evers called for, it also uses a different formula to distribute aid. The old criteria for distributing aid —which Evers’ plan rehabilitates— relied largely on “aidable revenues,” a measure based on local governments’ net revenue effort, their per capita property wealth, and population.

Assembly Republicans’ formula for municipal aid relies exclusively on population, but assigns a slightly larger multiplier to communities with populations under 5,000.

That formula, when combined with the overall smaller size of the Assembly Republicans’ package, has some significant consequences for the kind of aid communities receive.

Milwaukee County

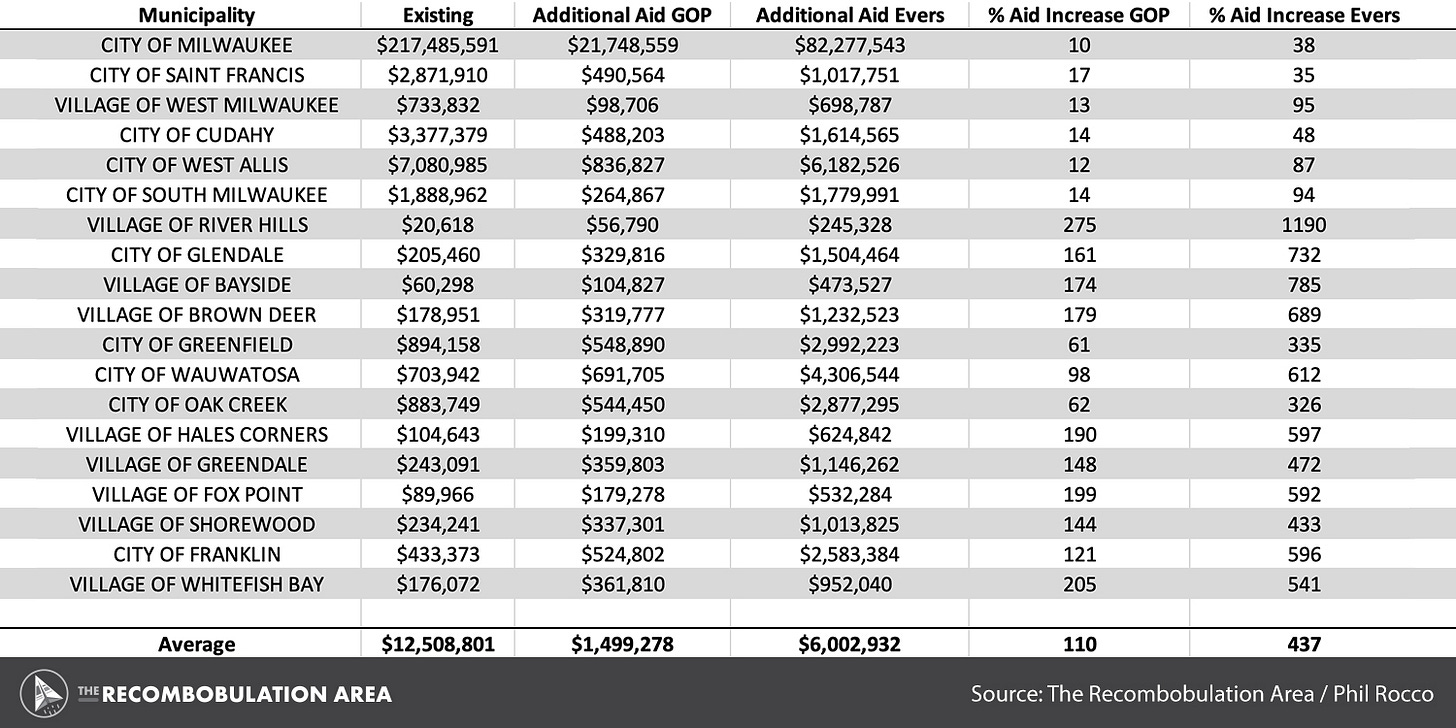

Let’s start by zooming in on municipalities in Milwaukee County. The table below looks at the aid received by each municipality today, the additional aid each municipality would receive under each plan, as well as the percentage increase.

One thing we can see straightaway is that under Evers’ plan, state aid increases are on average four times higher for Milwaukee municipalities than they are under Assembly Republicans’ plan. Keep in mind that under Evers’ plan municipalities will also have more flexibility in how this aid is spent. Whereas over half of the additional aid in Evers’ plan is “general purpose,” the additional aid in Republicans’ plan can only be spent on police, fire, and EMS services, and there are strings attached. Yet even if these restrictions did not exist, municipalities in Milwaukee County would receive far more under Evers’ proposal than they would under the current version of the Assembly Republican plan.

To be sure, neither the Assembly’s proposal nor the Governor’s includes shared revenue alone where the City and County of Milwaukee are concerned. As noted previously, both proposals also create a window of opportunity for increasing sales taxes in Milwaukee, yet the structure of each is slightly different.

Under Evers’ plan, Milwaukee County voters could—through a referendum—decide to impose an additional 1% sales tax, half of which would be shared with the City of Milwaukee. Beyond that, both governments would have autonomy in deciding how those funds are spent. Under the GOP bill, the sales tax would work differently. The City of Milwaukee could—if voters approve it in a referendum—impose an additional 2% sales tax. If a separate county-wide referendum passed, Milwaukee County could impose a sales tax of 0.375%.

Unlike Evers’ plan, however, those new sales tax revenues could only be spent on paying unfunded actuarial accrued liability of the county’s retirement system and for public safety services. And then, of course, there are the numerous restrictions on how the funding can be used (see my last post for more).

The Milwaukee Metro

Now let’s zoom out a bit to look at the eight counties that make up the Milwaukee – Racine – Waukesha Combined Statistical Area.

The graph below looks at the average increase in aid for municipalities in each county under each plan. Here we can see that but for the two least populous counties in the metro area––Dodge and Jefferson––municipalities do far better on average under Evers’ plan than they do under the Assembly Republican bill. In Waukesha County, state aid to municipal governments increases by nearly 450% under Evers’ proposal––double the size of the increase under the Republican plan.

The State

Now let’s zoom out even further to look at how things break down across the entire state.

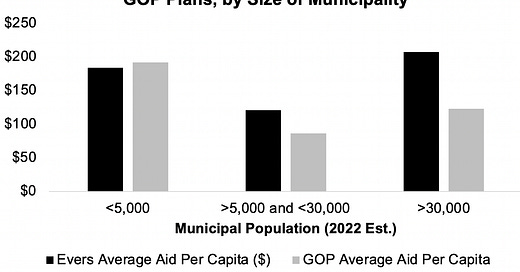

As I mentioned previously, one of the major distinguishing features of the Assembly GOP formula is that it assigns a slightly higher population multiplier to municipalities with smaller populations. To capture this, I broke down the average percent increase in municipal aid by each of the three population classes used by the Assembly GOP formula.

Here we see that the only class of municipalities that see larger increases under the GOP bill are those with populations less than 5,000. Even municipalities with populations between 5,000 and 30,000 would see a 142% increase under the GOP bill as compared to a 267% increase under Evers’ proposal.

The greatest discrepancy is among the largest communities, those with populations over 30,000 (there are currently 26 cities that fall into this category). Under the GOP bill, these municipalities would see on average a 43% increase in state aid. Under the Evers bill, the average increase is over five times higher.

The differences are similarly stark when we compare the average per capita aid municipalities would receive following the passage of each bill. Again, while the smallest communities fare slightly better on average under the GOP measure, those with a population of over 5,000 fare far better under Evers’ proposal.

Why It Matters

Understanding the distributional effects of these two proposals helps to capture how the gains from the state revenue bill will be shared by communities around the state. No less than any other area of Wisconsin politics, the design of a state revenue sharing program affects —in the immortal phrase of political scientist Harold Lasswell— “who gets what, when, and how.”

Republicans’ formula does not merely hit “restart” on the old revenue-sharing system, it reworks the logic of the system by abandoning the principles that defined how shared revenue payments went out for decades. When combined with the large number of new conditions added to state aid, the Assembly GOP bill represents a pretty fundamental reimagining of how the state-local revenue system would work.

This matters because, especially given the severe state restrictions on how local governments can raise revenues – already, sales and income taxes are preempted and property taxes are constrained by levy limits – state aid is one of the most significant sources of municipal finance.

The stagnation of state aid in recent decades has thus helped to lock cities into a vicious cycle. To take just one example, prior to the passage of the American Rescue Plan Act in 2021, the City of Racine faced a structural deficit of $6 million per year. An important contributor to this deficit was the decline of state aid. Were the City of Racine to receive the same amount of aid it did twenty years ago, adjusted for inflation, it would see an additional $20 million today. Under the Assembly GOP plan, however, Racine receives only the minimum 10% increase in aid. This amounts to just under $2.5 million in additional aid. Under Evers’ plan, Racine would receive an additional $12 million.

The differences between these two funding levels is not marginal––it cuts to the core of whether Racine will be able to support essential services that affect its residents’ quality of life.

What Now?

As of now, Gov. Evers has threatened to veto the Assembly GOP legislation in its entirety, citing concerns about both the inadequate size of the package and the number of conditions or strings attached to the measure. For the record, Evers won’t be able to use his line-item veto here. Republicans styled the shared revenue bill as a standalone piece of legislation rather than as a part of the state’s biennial budget. Evers’ ability to wield the line-item veto pen is limited to the budget bill.

The question now is the extent to which Evers’ veto threat induces legislative bargaining in the three major areas in which the bills differ on a statewide level (size, allocation formula, strings attached) as well as on the provisions that apply exclusively to Milwaukee. My guess is that we will see at least some movement here, though it’s hard to say how much or on which elements of the proposals. To date, Republicans’ proposal has received pushback from local officials on either side of the partisan divide. Yesterday, Milwaukee County’s Intergovernmental Relations Committee passed a resolution calling for “increasing shared revenue to counties and municipalities to fund local services with full autonomy and without restrictions from the State of Wisconsin.” As far as one can tell from state lobbying reports, the most important stakeholders’ positions on the Assembly bill are mixed.

Republicans seem to be banking on the idea that local governments will prefer marginal increases in aid and a significant intrusion on their autonomy to the status quo of stagnant state aid. The question is whether local officials across the state can exercise leverage to demand a “clean” revenue sharing bill that restores the logic of a century-old system rather than installing a new one that would be laden with more onerous restrictions and far less aid than communities are due.

Correction: A previous version of this story said that populations between 5,000 and 30,000 would see a 155% increase under the GOP bill as compared to a 267% increase under Evers’ proposal. Additionally, that previous version also said municipalities would see a 60% in state aid, and that under the Evers’ bill, the average increase is over four times higher. Those numbers have been corrected in the above article, under the subsection on “The State.”

Phil Rocco is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Marquette University. He is the author of Obamacare Wars: Federalism, State Politics and the Affordable Care Act (University Press of Kansas, 2016) and editor of American Political Development and the Trump Presidency (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020).

Subscribe to The Recombobulation Area newsletter here and follow us on Facebook and Instagram at @therecombobulationarea.

Follow Dan Shafer on Twitter at @DanRShafer.

Thank you for doing what you do. 🙂🙂