Looking Down the Road: What Does the Future Hold for the I-94 East-West Expansion Proposal in Milwaukee?

Part II of The Recombobulation Area's "Expanding the Divide" series takes a closer look at where the rubber meets the road for the proposed highway expansion in Milwaukee.

The Recombobulation Area is an award-winning weekly opinion column by veteran Milwaukee journalist Dan Shafer. Learn more about it here.

“Expanding the Divide” is a multi-part series on the proposed expansion of the 3.5-mile East-West corridor of Interstate 94 in Milwaukee.

Read the introduction to the series here.

We have arrived at a juncture where the opposition to this project warrants greater examination.

Read about that opposition in Part I of the Expanding the Divide series here.

Here in Part II, we are taking a closer look at where the rubber meets the road in this project. Hear from WisDOT officials, expansion supporters, political leaders and more about the reality of what’s happening with this project as it moves forward.

There’s a problem at the crux of the argument that we should be funding public transit instead of highway expansion.

Because of the way these projects are structured, the federal funding that would be available for this highway project wouldn’t be available to go toward an alternative public transit project.

So says Craig Thompson, Secretary-designee1 of the Wisconsin Department of Transportation (WisDOT). In an interview with The Recombobulation Area, Thompson said that the Evers administration would “agree with the overall standpoints” of the effort opposing highway expansion, and that he recognizes that there is “an imbalance in transit in the state, specifically in Milwaukee, between transit and road infrastructure.” But, the “devil gets into the details.”

“We are trying to find pathways to get more funding for transit, but I do think one of the misconceptions has been that we could reallocate some of this money that would go to this project for transit,” said Thompson. “That is not possible.”

Much of the interstate funding comes through federal dollars and is specific to highways and can’t be diverted by the state of Wisconsin toward the type of public transit or local roads improvement projects that highway expansion opponents seek.

“If we would go with the less expensive option here, that money is not fungible,” said Craig Thompson, secretary-designee of the Wisconsin Department of Transportation. “We could not use the delta to fund transit or local roads. That's not the way it works. The money we’re getting from the federal government is project-related funding. It’s federal highway money. What they don't spend there, they’d spend on other federal highways. On the state side, we're using largely bonding dollars, but whatever we would use, we’d have to get approved by the legislature. We can’t just unilaterally fund transit at a level that we would like.”

The path toward funding transit with state dollars is through the state legislature, he said.

And the Republican-controlled state legislature is not on board for transit funding — especially not for Milwaukee. The Joint Finance Committee just voted to cut funding for transit in Milwaukee in half over the next two years.

The reason cited was the influx of federal funding due to arrive from the American Rescue Plan Act, even though the Milwaukee County Transit System was already enduring cuts before the pandemic, and faces significant long-term structural challenges, like so many things in the local control-deprived county government structure in Wisconsin.

But federal funding could be set to make an impact on highways, too. Funding from the infrastructure bill being introduced by the Biden administration could go toward the types of modernization improvements that all sides agree are needed on the highway, said Thompson. But that bill is still tied up in Congress, and it’s impossible to say right now how it could impact this particular project.

CHANGING TIMELINES: A NEW SUPPLEMENTAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT DELAYS THE PROJECT

While things have been in flux at the federal level, one aspect of this project did see a significant change in recent months. The state is delaying construction to 2022. WisDOT announced Apr. 15 that it would be undertaking a supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) on the project.

Opposition groups celebrated the decision. Many of those opposing the project had been pushing for such a move, as the existing EIS had been completed before then-Gov. Scott Walker had cancelled the project in 2017. And for that EIS, said Cheryl Nenn of Milwaukee Riverkeepers, “they didn’t even look at any non-expansion alternatives.”

The supplemental EIS announcement came down just days after highway expansion opponents met with federal officials from the Biden administration.

“We had a really good meeting with the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and I think they are supportive of doing a better job with the EIS,” said Nenn, who has been active with the opposition effort. “We see that as a small win that we had, that FHWA is requiring WisDOT to require them to go back and do a supplemental EIS. That's a small victory...We’re happy that they’re doing additional research on the traffic impacts and the climate impacts. But often what happens is that this could just be delaying things for a year. They’ll sign the highway expansion stuff necessary (in the state budget) and they’ll have the funds ready to proceed when they’re done with the EIS. We’re still really concerned about it.”

Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett, too, supported the supplemental EIS, as did Milwaukee County Executive David Crowley, in an interview with The Recombobulation Area.

“It’s important to remember that this project is being reevaluated,” Crowley said. “This isn't necessarily the same proposal that we have seen before. So for me, it’s really making sure that we give folks the opportunity to talk more about this. I really appreciate WisDOT asking for the supplemental EIS on this project because it is going to allow us to do a deeper dive into traffic patterns, into roadway efficiencies, but also the safety of this particular highway. It’s going to allow for more general input from the public. At the end of the day, we want to assess all the data. Whatever happens when we look at this EIS, if (the expansion) moves forward, it has to be safe for this community, it has to be efficient, and it has to be beneficial to the entire community.”

Crowley would not say whether or not he supported adding lanes to the highway, instead stressing the need for the type of community discussion that the supplemental EIS promises to allow for.

“For me, it's really about making sure that we are methodical and strategic on how things happen in this community,” he said. “That’s one of the reasons why I need certain questions to be answered before I can say that I support or that I'm against the project.”

Part of that conversation, he said, is a way to talk about “how do we right the wrongs of the past” as it pertains to highways in Milwaukee.

“When you think about highways, when they were built, they were used to divide communities,” he said. “They were used to segregate communities here in Milwaukee. For me, I would like to figure out ways to connect communities.”

Thompson, too, acknowledged the history of highways and the way in which they divided communities.

“When the interstate system was built in the ‘50s and ‘60s, for all the good that it did in terms of economic competitiveness, it was laid down in a way that communities of color were not consulted and it did divide communities,” he said. “The way interstates were laid down throughout the country, including here in Wisconsin and Milwaukee, we are still seeing negative ramifications from that today.”

Thompson said the Evers administration is committed to a robust public engagement process over the next year, hoping for more in-person discussion. The supplemental EIS will allow WisDOT to “take our time,” particularly as a way to analyze “real-time data, not pre-covid data.”

“We want to make sure we’re giving everybody the opportunity to weigh in,” he said.

It is going to be important for people to get involved in this process as it unfolds over the next year, and it is going to be extremely important for WisDOT and the Evers administration to make good on their pledge to ensure the type of public process that a billion-dollar project like this demands.

FROM EAST TO WEST: BREAKING DOWN THE PROPOSED PROJECT

So, when you get to the ground level of this reconstruction and expansion project, what exactly is being proposed?

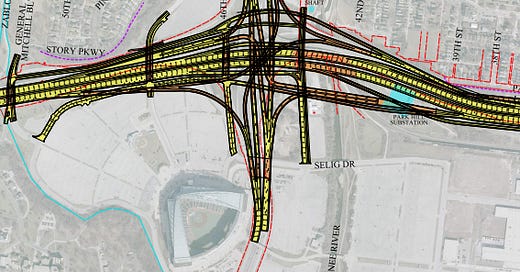

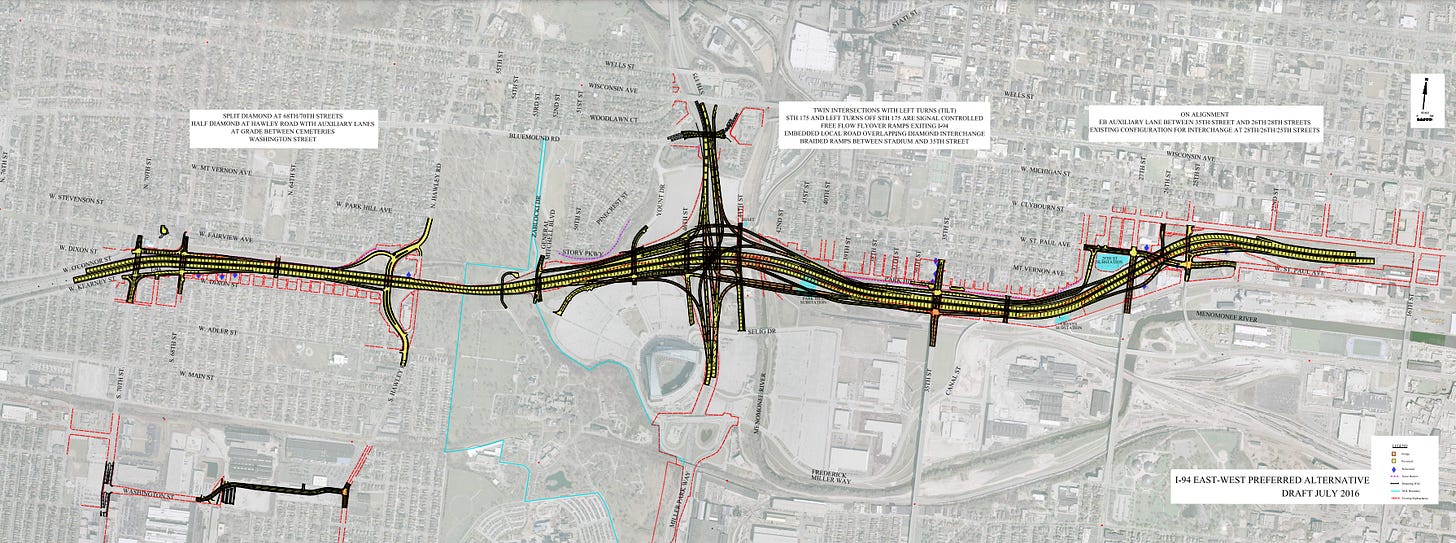

The map you see here was provided to The Recombobulation Area during the reporting of this article in response to a request for the most up-to-date visual breakdown. The draft reads that it is from July 2016.

Let’s take a closer look at what’s happening in the images below.

From West to East:

Along with the major reconstruction of the stadium interchange where I-94 meets Wisconsin Highway 175, Thompson said the project would eliminate eastbound on-ramps at Hawley Road, making it half an interchange, eliminate the left-hand exit at Mitchell Boulevard, and add an additional eastbound auxiliary lane between 35th Street and 27th Street. Five “service interchanges” would be rebuilt -- 70th-68th, Hawley Road, Mitchell Boulevard, 35th Street and 26th Street/Saint Paul. With the expansion, instead of merging down to three lanes, the lanes in the four-lane option would narrow at a cemetery that sits on both sides of the interstate near Miller Park. Previous versions of the plan discussed the option of moving the graves at the cemetery, but that would not happen in the current proposal.

“We did try to make as many changes here to really minimize our footprint and impacts,” said Thompson. “So, the amount of takings that we would have as a result of this — we’re still working — but we’ve got it down to a handful of businesses and residences, which for a project like this is really quite minimal.”

But here’s what highway expansion opponent Michael Bradley, co-host of NEWaukee’s Urban Spaceship podcast, had to say about the interchange-by-interchange breakdown of these plans.

“Let’s walk through why this project just is terrible for Milwaukee,” he said. “Let’s go from west to east. Hawley Road no longer gets access going east to downtown. Those lanes that are currently used by people on the west side (of Milwaukee) to go downtown become the fourth lane to get through the pinch point at the cemetery. Hawley Road gets sacrificed for the betterment of commuters that are further out. Then, you get to the stadium interchange. You redo the stadium interchange in a design that the community has said isn't what we want...Then you get into the Pigsville and Merrill Park and Avenues West (neighborhoods) and the communities that are directly affected, and what do we do? You’re taking more homes and businesses in a place where the highway has already demolished so much of the community. Then, you get to 35th Street and they’re not making any improvements to the exit. I don’t know if you know the 35th Street exit -- it sucks. Then you get to the 27th Street exit, and it’s the worst exit in metropolitan Milwaukee. They’re not changing it. Then you’re at the Marquette freeway. That’s the three miles you’re talking about. At every juncture, it’s a bad deal.”

Thompson said the non-expansion option is something WisDOT is “still looking at,” but the big picture comes down to this:

“We’ve got 3.5 miles of interstate in the busiest area of our state, right there in front of AmFam Field now, which connects two areas of the interstate that have already been completed — the Marquette Interchange and the Zoo Interchange — we’re (currently) completing the north end of the Zoo. So there’s 3.5 miles in between. And where I think there is agreement that everybody has coalesced around is that it needs to be rebuilt. We can’t resurface it again, it just wouldn’t last and we’d have constant orange barrels. So the question comes down to, when we rebuild it, do we do some of the improvements to get rid of the left-hand exit and some of the things we would have to do to bring it up to current standards, but do it within the current amount of lanes? Or, do we rebuild it and while we’re doing that, add the lane in each direction?”

As he sees it, the key issue is safety.

“If we rebuilt this at six (lanes), you would have the merging going both ways,” he said. “Right now — I’m not saying it’s 100% because of the merging; there are other safety issues with some of the exits and things — this stretch of interstate has crash rates 2.5 times the average. It’s one of the most dangerous stretches. If we’re going to spend hundreds of millions of dollars to rebuild it, we want to make sure we’re doing it in a way that we’re going to improve safety.”

WHO SUPPORTS EXPANSION?

Steve Baas, senior vice president of governmental affairs at Metropolitan Milwaukee Association of Commerce MMAC, the region’s largest business lobbying group, has been a lead spokesman for the coalition in support of widening the highway.

In March, Baas wrote an op-Ed — “The Road to a Brighter Economic Future” — at 620 WTMJ in support of the project, speaking as a member of “I-94 East West Econ Connect,” a group that includes the MMAC, Commercial Association of Realtors Wisconsin (CARW), Marquette University, Menomonee Valley Partners, MillerCoors, Potawatomi Hotel and Casino, Waukesha County Business Alliance and Near West Side Partners. Other supporters of the expansion effort include a number of suburban mayors and several labor unions.

In an interview with The Recombobulation Area, Baas said that what necessitates the extra lane is that, in contrast to the way he characterized those opposing highway expansion, “We are probably a little bit more optimistic about Milwaukee’s future.”

“We see this as a region on the rise, a growing region,” he said. “If we’re going to grow, we’re going to also have to grow our capacity to accommodate that growth. If you’re going to put WiFi in your house, why wouldn’t you put in the broadband? Why would you put dial-up in instead? If we’re going to be investing hundreds of millions resurfacing and reconstructing this roadway, why wouldn’t we do it with the capacity to accommodate a growing economy, for a future that we’re pretty bullish on in terms of the capacity for growth here in metro Milwaukee?”

While many opponents of highway expansion say fewer cars on the road should be a larger goal of any 21st century transportation project, Baas sees this differently.

“Fewer cars on the road is less economic activity and fewer people in the long run,” he said. “That has both economic and quality of life impacts. Some people would like to keep Milwaukee, put a pin in it in its size and its vitality that it has right now, and some people have a more bullish vision for the future.”

While Thompson and other I-94 expansion supporters are also seeking ways to bolster transit options in tandem with the highway widening project, Baas’ “bullish vision” for Milwaukee’s future does not include expanded options for public transit. His views of transit in Milwaukee — and public transit, in general — are not positive.

“For transit in Milwaukee, ridership continues to decrease,” he said. “The market demand for transit in Milwaukee has got a problem. The transit system and the County leaders need to really take a look at whether that is the function of the routes and the route design or whether that’s a function of people’s choices. And if it’s a function of people’s choices and preferring a more flexible mode of transportation rather than a fixed-route mode of transportation, then the response to adapt to that is one thing. It’s clear that Milwaukee's transit system has not been seeing increases in ridership. People have been voting with their feet not to use it. You need to look at whether that's just individual preference or if it’s a systemic problem that needs to be addressed within MCTS. (Declining transit ridership) is not unique to Milwaukee either. It’s happening in most of the major metros in Wisconsin right now.”

Another part of his support for expansion is what he called “regional mobility.”

“Summerfest would like people to be able to get downtown easily,” he said. “The Bucks, the Brewers, the symphony, the ballet. Making it easier for more people to come to Milwaukee, use Milwaukee’s amenities and leave behind their hard-earned money and fuel the Milwaukee economy is something that’s beyond a global economic perspective, it has a very parochial positive impact on the city, too.”

The MMAC has also been supportive of another currently-in-flux state level proposal, backed by local leaders and introduced by Gov. Evers, to grant local governments like Milwaukee the option to raise its own sales tax. Assembly Speaker Robin Vos recently said this will “never happen.”

But Baas said that adding lanes would be a way to “(expose) more people to the amenities of Milwaukee” and “create an awareness and demand for the local funding source issue.”

“If Milwaukee is an abstract idea to outstate legislators, they’re not likely to invest in raising taxes to support Milwaukee,” he said. “If Milwaukee is a real concrete idea to them that they can relate to, and these amenities that we’re trying to help fund are things they can relate to, they’ve participated in, or they can appreciate, I think that actually creates some more positive momentum for that discussion. The fewer people who can experience Milwaukee, the harder it is to get there, the more Milwaukee isolates itself logistically, the harder it is for people to understand the value and the amenities in Milwaukee. The more you can get down there, the more concrete the benefits to people from outstate. The less you do that -- if you don’t expand capacity, if you continue to have a choke point there -- that could create a disincentive for people coming to Milwaukee.”

Despite his central role speaking in favor of this proposal, Baas is perhaps an unreliable spokesman for this or any project. His past involvement in working to spread election fraud conspiracy theories with Republican legislators and other conservative operatives in 2011 is undoubtedly problematic. Last year, plans for Baas to lead the Board of Directors at Visit Milwaukee, the region’s visitors and convention bureau, were scrapped after many objected to the move, and that was before months of election fraud conspiracy theories called into question the legitimacy of votes in the city of Milwaukee.

Baas also disagreed with the notion that highway projects have further segregated Milwaukee, and when asked about the Zoo Interchange settlement that deemed the project racially discriminatory and if that would also be a concern with this project, he said, “There are always people who will try to leverage some additional money or settlements out of any of these projects.”

A VEHICLE FOR MULTI-MODAL TRANSIT AND ADDRESSING THE “SPATIAL MISMATCH”

If there’s a middle ground between expansion opponents and advocates, it’s in the space occupied by Dave Steele, executive director of the Regional Transit Leadership Council, who wrote an Urban Milwaukee op-Ed on the East-West corridor project called, “I-94 Rebuild Could Be Multi-Modal Success.”

Steele wants to see this project used as a vehicle to advance a shift toward multi-modal transportation in the Milwaukee metro area, and says a project of this size and scope presents opportunities to do just that.

“We’re at this point now in the region in Milwaukee where they did the Zoo Interchange, they did the Marquette Interchange, they did the Mitchell Interchange, they got 94 south of Milwaukee, and this is pretty much the last big mega project,” he said. “A lot of folks use that corridor for travel between Milwaukee and Waukesha counties, and that includes people riding transit and biking and walking. And it’s a two-way street, it’s not only city people going out to the suburbs or suburban people going out to the city; it’s really a 50-50. Let’s seize upon opportunities that could come around from this kind of project that could really put a shot in the arm of some viable projects that could really move multimodal transportation forward.”

Steele says that while the future needs to be more multi-modal, the current landscape for getting around in Milwaukee is still very much dominated by cars.

“The fact is that outside of the core city of Milwaukee, things are really really car-oriented,” he said. “That really induces demand for driving everywhere. Rebuilding I-94 at six lanes, I don't know that that additional lane in a grand scheme would really make that huge of a difference in encouraging even more driving. I understand the desire to draw a line and say “no more expansion,” but I prefer to look at it in the sense of: what can we get in the here and now to alleviate the transportation mismatch we have in our region? Most of the jobs in southeastern Wisconsin are outside the scope of transit right now. Pre-pandemic, almost 20% of city of Milwaukee households didn’t have cars. That’s significantly higher than the national average and much higher than our peer Midwestern cities. A lot of people are surprised to hear that figure that that many Milwaukeeans get around without cars...In a region where the majority of jobs are outside of bus routes, that's a significant hindrance to economic mobility.”

The “spatial mismatch” the region grapples with — referenced in the introduction to this series where a significant shift in the racial demographics of the city and region occurs with each commute — is something Steele says needs to be a priority in these projects to promote economic mobility.

“Our priority is really addressing that spatial mismatch,” he said. “How do we implement solutions that are relatively shovel-ready that can be implemented relatively quickly to make those connections happen and help alleviate the hindrance to economic mobility due to our spatial mismatch.”

Part of that opportunity for a transit project or multi-modal project that could aim to address that spatial mismatch and would be through federal traffic mitigation dollars that are often paired with highway projects like what’s being proposed.

Thompson said that WisDOT will be “aggressive” about working for mitigation dollars to go toward transit, especially as federal funding for infrastructure takes steps forward.

“The Biden administration put money into (its infrastructure bill) to help areas that were historically divided by interstates — $20 billion, I believe — and we are going to do everything we can to look at how we can make the best case to use some of that money in Milwaukee, as well,” he said.

Thompson also said WisDOT is already working with Milwaukee County to identify certain routes that would build key connections for city residents, and mentioned the Hank Aaron State Trail, the 27th Street corridor, and other enhanced bus routes as potential options.

Groups like the Wisconsin Bike Fed who oppose expansion could shift focus to mitigation funding if highway expansion ultimately goes forward.

“If this project goes along, we have to switch gears,” said Caressa Givens, Milwaukee advocacy and projects manager at the Wisconsin Bike Fed. “We have to squeeze the most out of the orange, so to speak, in terms of what that mitigation funding could allow. We can’t say that it's inevitable, it has to happen concurrently.”

BRT: “ONE OF THE BIGGEST INVESTMENTS IN TRANSIT IN OUR REGION IN PROBABLY 30 YEARS”

The county has already held several meetings to discuss potential for mass transit in the 27th Street corridor. It would involve an expansion of the existing Purple Line service that essentially runs north-south through the length of the county, from Glendale — past the 30th Street Industrial Corridor, the Mitchell Park Domes, Aurora St. Luke’s Medical Center -- to Oak Creek, ending at IKEA.

Many have suggested that as a location for a Bus Rapid Transit line, an investment Crowley said would be an important one.

“We have to invest in public transit,” he said. “If we don’t, we’re going to leave the same communities that have been historically underserved, historically marginalized, and those that have had highways built in their communities, we’re going to leaving many of those individuals behind if we do not invest in public transit.”

Crowley recently joined Gov. Evers, Rep. Gwen Moore, Mayor Barrett, and other federal, state and local officials at the intersection of 27th Street and Wisconsin Avenue to celebrate the groundbreaking for the region’s first Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) line, the East-West route.

“This BRT is a BFD,” Crowley said at the June 14 event.

The East-West BRT line will run nine miles from the lakefront -- starting with a station at the finally-under-construction Couture high-rise -- to the Milwaukee Regional Medical Center in Wauwatosa, one of the region’s biggest job centers that includes six campus organizations, including Froedtert Hospital and Children’s Wisconsin.

Construction on the East-West BRT is expected to finish in late 2022, and the line will use a fleet of all-electric buses, include 33 individual stations, dedicated bus lanes, will run with higher frequency, and take a total of 34 minutes to ride the route from end to end.

Steele says it’s “one of the biggest investments in transit in our region in probably 30 years.”

“That was a $54 million project and $45 million of it came from the U.S. Department of Transportation,” he said. “The project was first conceived when Obama was still president and had gone about 85% down the road before it was announced by the previous president in a tweet. But it’s just a start. It goes from downtown Milwaukee to the medical campus. It’s entirely feasible to essentially extend that in some sort of rapid bus link to take that right down Bluemound Road into the city of Waukesha. There are 24,000 jobs between 124th Street and the city of Waukesha along Bluemound Road, and MCTS already serves Brookfield Square with the Gold Line -- it’s one of their higher performing routes. The political leadership in Waukesha County is fully supportive of a bus connection to Bluemound Road.”

Steele said it’s important that business leaders are seeing the benefits of investing in these regional transit connections like BRT, and that we need to start getting less political about transit in the Milwaukee area.

“We have to decouple this from politics,” he said. “Some of the most Republican-oriented conservative states and cities around the United States have really gone all in on multi-modal transportation. Salt Lake City is one, Oklahoma City has started a regional transit authority, Indianpolis has gone all in on bus rapid transit, Kansas City, Columbus, these are places that are very conservative. Here, in our region, with a lot of things that have happened over the last 10-15 years, transit does tend to be a bit more politically divisive. It's incumbent upon us that we want to see more multi-modal to present a value proposition to the business community that really depoliticizes it. And that this is good for economic development, this is good for workers. Setting it up so that more people in Milwaukee can access job opportunities in the suburbs is good for economic development in the suburbs and the city and the whole region because more people working is better for economic development.”

As evidenced by the most recent presidential election, the region that was once characterized as the most politically polarized in the nation is becoming less so. Suburban regions, particularly in Waukesha and Ozaukee County, have shifted to the left, and are now more balanced than in previous years when the suburbs were overwhelmingly dominated by Republicans. And in the city of Milwaukee, some of the more pronounced shifts that occurred in 2020 were moves to the right, with majority-Hispanic neighborhoods on the city’s south side voting more Republican than ever before.

Perhaps the polarization in the region is beginning to melt, and perhaps this issue of multi-modal transportation and regional economic mobility could emerge as a place where the Milwaukee metro finally comes together to seek meaningful solutions. Or maybe the MMAC’s approach will win out, and this debate will end once again with Milwaukee doubling down on car culture, kicking transit to the curb.

But as this conversation unfolds by way of state-level the supplemental EIS, county-level discussions about the next BRT line, a larger community discussion about economic mobility in a time of labor shortages, wage stagnation and spatial mismatches, people are going to need to get involved and make their voices heard on this issue.

The addition of the supplemental EIS, the changing approach of the federal government toward highway projects, and the infrastructure bill potentially making its way through Congress amplifies the importance of the discussion about the proposed I-94 expansion project.

Although state leaders from both parties currently support this project, as it stands in 2021, it is far from set in concrete.

It is imperative that Milwaukee and Wisconsin take this conversation seriously, and that the robust public process that’s promised through the addition of the supplemental EIS materializes in a way that addresses so many of the legitimate concerns raised by expansion opponents.

The likely outcome remains the likely outcome. But this is a $300 million conversation. It is not one to be raced through. And it’s not over. Milwaukee needs to decide whether it’s going to be modernization or expansion, and what its future is going to look like, and what our priorities are going to be.

Coming soon: Part III

Subscribe to see the final part of “Expanding the Divide.”

Dan Shafer is a journalist from Milwaukee who writes and publishes the award-winning column, The Recombobulation Area. He previously worked at Seattle Magazine, Seattle Business Magazine, the Milwaukee Business Journal, Milwaukee Magazine, and BizTimes Milwaukee. He’s also written for The Daily Beast, WisPolitics, and Milwaukee Record. He’s on Twitter at @DanRShafer.

Subscribe to The Recombobulation Area newsletter here and follow us on Facebook at @therecombobulationarea.

Follow Dan Shafer on Twitter at @DanRShafer.

Craig Thompson, the former executive director of the Wisconsin Transportation Development Association, has served as the Transportation Secretary in the state of Wisconsin since Tony Evers became governor. The Republican-controlled State Senate, which confirms cabinet appointees, has not yet confirmed Thompson’s appointment. This has become a pattern in the State Senate since Tony Evers became governor. Andrea Palm, the former secretary-designee of the Department of Health Services, served in the role for two years and led the state’s pandemic response before departing to become the deputy secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in the Biden administration. She was confirmed with bipartisan backing in the U.S. Senate despite never being confirmed in the Wisconsin State Senate.

This issue may never have existed if I-894 had been constructed as a full by-pass around Milwaukee.

There should have been another roadway running east-west from I-43 to Hwy 41/45 in the area of the Milwaukee County/Ozaukee County line. Of course the forces wielded by the population of that area greatly exceeded the power of the people in Milwaukee whose homes and neighborhoods were ravaged in the name of progress.