Whose Cream City?

Only a narrow slice of Milwaukee votes in mayoral elections, but it wasn’t always this way. Guest essay by Marquette professor Phil Rocco.

The Recombobulation Area is a six-time Milwaukee Press Club award-winning weekly opinion column and online publication written and published by veteran Milwaukee journalist Dan Shafer. Learn more about it here.

The Italian Community Center is a squat, nondescript building located at the edge of the Third Ward where cityscape meets freeway, in a zone of industrial warehouses that feels like a studio backlot for the movie that is Milwaukee. On a Monday, in the Center’s main ballroom, two mayoral candidates wait to be called to the stage for a debate which few outside of Milwaukee’s business and philanthropic elite will — in a way befitting the contemporary mode of urban politics — even be likely to hear about.

They will not hear about it because it is not a debate meant for the ears of most Milwaukeeans. And it is not for their ears because the mayoral election is not a contest whose outcome the average Milwaukee resident will likely help to decide.

The crowd in the ballroom is wearing business attire. They finish their lunches as coffee is served. Before introducing the candidates, Tim Sheehy — President of the Milwaukee Metropolitan Association of Commerce, one of the event’s hosts —reminds the audience that his organization was founded only 15 years after Milwaukee’s incorporation, and, more pertinently, that he has worked with the last four mayors to ensure that they understood the relationship between a prosperous city and its surrounding economy. He concludes by thanking each candidate for “stepping up” to run.

This is not the kind of public event that packed Turner Hall with attendees before the February primary. But its atmosphere — simultaneously clubby and frosty — is far more representative of what mayoral elections have become in the United States. Just 22% of the city’s registered voters turned out in the February primary weeks earlier — a number on par with similar elections around Wisconsin, and with off-cycle elections around the country.

The low turnout does not reflect low electoral stakes. The mayor plays a pivotal agenda-setting role in defining how the city’s nearly $1.7 billion budget will be spent.

Nevertheless, if the past is prologue, few of the city’s residents will participate in this election. Between 2000 and 2020, mayoral turnout as a percent of registered voters was, on average, 35%. And as an abundance of political science research suggests, participation in local politics generally skews towards the wealthy, the white, and the propertied. And as the electorate becomes skewed, public policies begin to reflect the abstract world of the condo dweller rather than the needs of people who spend winter mornings waiting for the bus or digging out their cars.

It does not have to be this way, of course, because it was not always this way.

1.

You can tell a lot about a government by how it keeps records about itself. By the middle of the 20th century, after several successive decades of Socialist mayors, Milwaukee had become a beacon of good governance, public infrastructure, and efficient management. The character of the city’s records testify to this fact. And the records of the city’s Board of Election Commissioners are no exception. It is not surprising to find a city that placed the lives of its working class at the forefront of policy-making would also document its elections in slim, handsome volumes––all of which feature elaborate tables describing who registered, who voted where and for whom.

Nor is it surprising that Milwaukee’s election officials would have been proud of their elections, because the turnout rates were so remarkable.

The mayoral election of 1936 is a case in point. This was the race that returned Mayor Dan Hoan––the longest serving of the city’s “Sewer Socialists”––to power for a final term after a vigorous contest against Milwaukee County Sheriff Joseph Shinners. As the table below shows, turnout as a percent of registrants was 84% for the city as a whole. What is significant here, however, is that turnout across all wards was extraordinarily high. The ward average for men was 87% and for 80% for women.

This high rate of turnout across all 27 wards is significant for several reasons. Above all, it illustrates that––while there was a slight class bias in the electorate––it was far weaker than the one that exists in most contemporary mayoral elections.

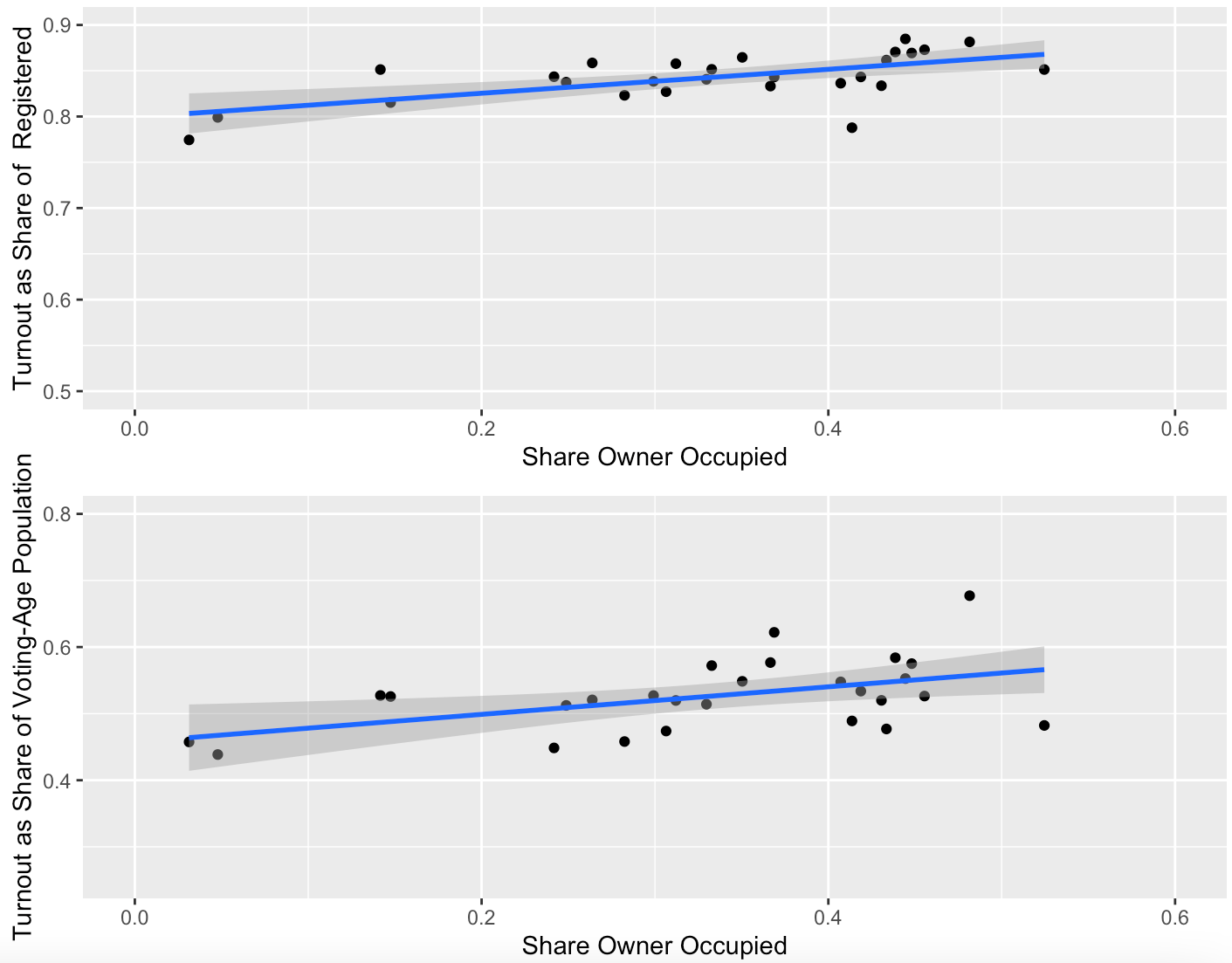

It’s easy to see this when we examine the relationship between homeownership and turnout. As the charts below suggest, whether we measure turnout as a percent of registered voters or as a percent of the voting-age population, there is essentially no relationship between the percent of owner-occupied residences and participation in the mayoral election. Similarly, there is almost no link between the percent of a ward’s population that the Census classifies as “native-born” white and mayoral turnout in 1936.

The upshot of relatively high citywide turnout was that successful mayoral candidates relied on cross-cutting political coalitions that included a broad swath of the city’s working-class voters (one piece of evidence here is that Hoan received sizable vote shares from wards with both low and high levels of homeownership). Indeed, even wards densely populated with Catholics––whose residents had voted against Socialists in the past––provided a strong base of support for Hoan. Hoan maintained this coalition by making tangible improvements in public infrastructure and social services that earned them the nickname “Sewer Socialists.” By 1936 — the year Hoan graced the cover of Time magazine — Milwaukee boasted the nation’s largest municipally-owned educational system, the largest per-capita adult night-school enrollment in the country, and systems of publicly-run parks, playgrounds, social centers, beaches, and entertainment venues. Time hailed Milwaukee as one of the “best-run cities” in the country.

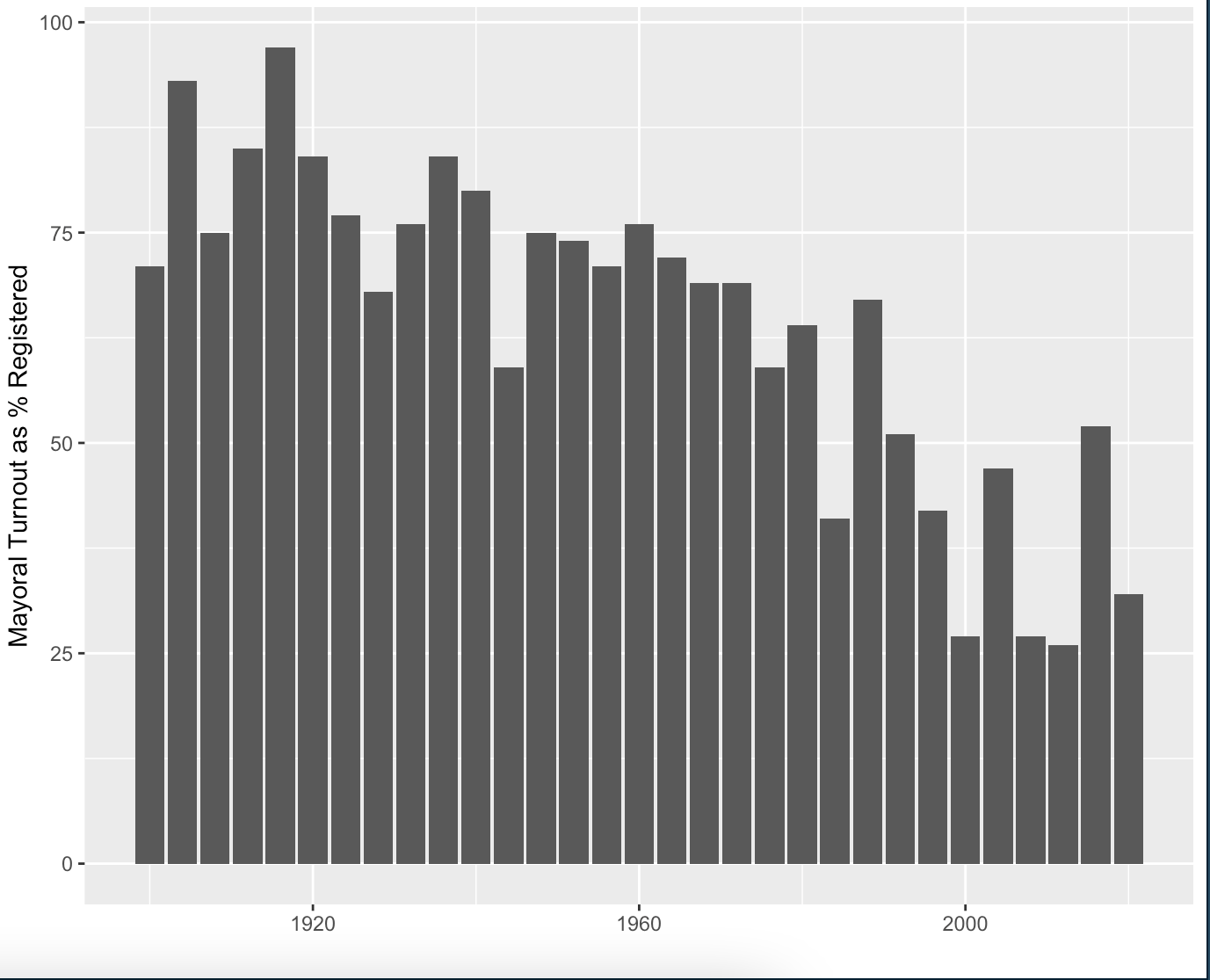

In the years since––and with increasing intensity since the 1970s––participation in Milwaukee mayoral elections has cratered. As the graph below shows, while the average turnout hovered north of 70% in the 1960s, it had fallen south of 50% by the 1980s. In the last two decades, mayoral turnout crested 40% only twice.

Flagging turnout reinforces a class bias in elections, weakening the link between the vast majority of the city’s residents and their elected officials. In a state whose legislature has made it famous for weakening democracy, turnout rates this low in an election for the chief executive of the state’s largest city should be a cause for concern.

So what happened?

2.

When thinking about what could be called the “democratic cliff” in Milwaukee mayoral elections, it’s tempting to turn the blame inwards — to find the unique features of elections in this city and state that might have contributed to the rolloff in voter turnout.

For example, we know that when cities hold their elections for local offices off-cycle — in Wisconsin’s case, in the spring of an even-numbered year rather than the fall —turnout almost universally falls (leaving aside what spring really means in a state with Wisconsin’s climate). Yet while moving local elections on cycle would almost certainly improve turnout, this explanation does not do the heavy lifting we need. That’s because all of the Milwaukee mayoral elections in the figure above were held in the spring. The same goes for nonpartisan elections, which are often cited as a cause of lower voter turnout, but which have been present in Milwaukee since 1912.

Another tempting explanation is Wisconsin’s status as a leader in the state preemption of local laws — ranging from regulations on fire safety to the minimum wage and worker protections — a policy trend which is almost calibrated to deprive local officials of the ability to make meaningful promises to their voters come election time. Yet while state preemption has no doubt taken turnout-generating issues off the ballot, it is less helpful in explaining the broader historical pattern of change––which began decades before Scott Walker and Republicans in the state legislature began their aggressive preemption push.

In short, all of these factors — nonpartisan races, off-year elections, and state preemption of local power — should be thought of as important accomplices to the crime of weakening democracy in Milwaukee. They impose real constraints on turnout, and enhance voters’ alienation from local politics. But the real culprits are to be found elsewhere.

3.

To understand the long decline in democratic participation, we have to start by recognizing that Milwaukee is not alone. In fact, voter turnout has declined throughout the democratized world since the 1960s (the 2020 U.S. presidential election was an exception to the rule). While political scientists have for decades debated the causes of this downward trend, most analyses converge on a set of changes in how politics works that have led voters to become more atomized and increasingly alienated from the material consequences of public policy.

One important factor has been the decline of traditional, locally-organized mass political parties. American political parties––while never strong, mass-membership organizations like their European counterparts––were once more locally-organized and connected to their mass base. While Milwaukee’s elections were nonpartisan, local parties were nevertheless crucial to election mobilization. They tended to be organized in a ward-based system, in which members paid nominal monthly dues and elected leaders from among their ranks. For example, in 1912, Milwaukee’s Socialist Party boasted 150,000 local members with 49 branch organizations in the city. Each party ward organization had its own chairman and ward organizations were often the birthplace of prominent candidates for office at the local and state levels.

The strength of party ward organizations was a key factor in turning out voters to participate in citywide elections. In many cities, local parties tended to accomplish this through patronage––trading votes for goods, services, or employment. Yet for insurgent mayoral candidates like Emil Seidel, ending this kind of corruption was a key electoral goal. One of his first acts after winning the 1910 mayoral election was to reorganize the city government “on an efficiency basis” with professional civil servants replacing political appointees––a move which attracted support not only from the party’s traditional base but from the city’s business leaders and middle-class voters as well.

Together with state-level anti-patronage measures, reforms like these weakened local parties’ ability to win votes through patronage. Instead, their success hinged on stitching together the votes of tight-knit ethnic communities beyond their core German-American base by building a reputation for improving the quality of life for the city’s working class through constructing public parks, libraries, schools, improving access to medical services, including postnatal care for infants and mothers, and reducing high rates charged by local utility companies. The city’s growing Polish population, concentrated in sections of the city’s north and south sides, proved a key constituency. Socialists cemented this reputation with voters by widely distributing publications like the Milwaukee Leader and the Polish-language Naprzód and through sponsoring street fairs and Sunday schools.

With local parties organized in this way, voters could more easily see politics not as a set of position statements, but a constellation of social relationships that could––under the right conditions––produce a better place to live. And even when things went awry, that set of relationships continued to encourage voting as a civic norm.

But it didn’t last.

Racism — as anyone familiar with Milwaukee’s history will know — is an important part of the story. Between 1950 and 1960, as a consequence of the Second Great Migration, the city’s Black population grew from 21,772 to 62,458. While Black Milwaukee still constituted a relatively small share of the city’s total population–– concentrated via racially-restrictive covenants into roughly four wards––their presence occasioned a contemptuous reaction from the white “city fathers.” The major parties did not operate ward organizations in Black neighborhoods — including those represented by Vel Phillips, the first Black member of Milwaukee’s Common Council. As a consequence, these wards had among the lowest turnout in citywide races. Unsurprisingly, when Black Milwaukeeans attempted to advocate for their rights, traditional party organizations were unresponsive — forecasting their own irrelevance in a multiracial city.

Citywide officials who were responsive to Black voters also put themselves in political jeopardy. This was the case for the city’s last Socialist mayor — Frank Zeidler — who, after spending the late 1950s trying in vain to secure Common Council support for affordable housing for newly arrived migrants, declined to run again in 1960. His successor, Henry Maier, rejected Zeidler’s plans to support infrastructural and service improvements to the city’s predominantly Black neighborhoods and refused to support open-housing legislation for the city by punting the issue to the county government. Maier, a Republican-turned-Democrat, did not budge from his stance against open housing, even in the face of a social movement which organized 200 nights of marches and protests. He was re-elected for the next two decades.

By 1968, traditional party organizations were straining under the weight of conflicts they had not been designed to manage, and which their central gatekeepers did not wish to manage. Their national conventions soon adopted a set of reforms to their nominating procedures that made local and state party leaders increasingly irrelevant. As local parties became hollowed out, they were replaced with lean, nationally-oriented organizations that organized local voters only when the federal election calendar demanded it, as well as a loose network of single-issue interest groups oriented towards achieving policy victories at the national level. Not only has this produced, in the words of political scientist Julia Azari, a country defined by weak parties and strong partisanship, it has also robbed local voters of a key conduit for political engagement and mobilization.

The result is lower turnout in city elections and, in turn, policy choices that disadvantage the vast majority of city residents. Unsurprisingly, Milwaukee still has one of the lowest Black homeownership rates in the country. And there is a powerful political feedback effect: renters are significantly less likely than homeowners to vote in local elections.

4.

In cities throughout the United States — especially highly segregated ones like Milwaukee — political conflict has long been divided along the lines of racial, ethnic, and territorial affinities. Forming solidarity across these “city trenches,” as political scientist Ira Katznelson calls them, has always required a deliberate organizational force. In Europe, labor parties constituted that force. In a country which has never had a nationally competitive labor party, accomplishing this solidarity and building electoral power — especially among disadvantaged groups — has hinged on the strength of the labor movement.

It is hard to overstate the importance of organized labor in the history of Milwaukee politics. From the formation of the Federated Trades Council — a local branch of the American Federation Labor — in 1887, workers formed the backbone of political movements in the city and the state. Not only did labor play a central role in coordinating political support for Socialist candidates in the early 20th century, the movement — through both bloodshed and political agitation — fundamentally changed the life of working people through the creation of the eight-hour work day.

By the 1960s, Milwaukee’s industries were almost completely unionized, with the Milwaukee County Labor Council organizing over 125,000 workers. The Council’s electoral unit, the Committee on Political Education (COPE), played a pivotal role in local elections. COPE provided extensive candidate endorsements and political news via the Milwaukee Labor Press, a 16-page weekly tabloid. The Committee also mobilized member participation in local elections––obtaining polling lists from the city’s election commission and checking them against union membership rosters to ensure that member registration and turnout were high.

With a high level of union density — which meant power on the shop floor and the ballot box alike — organized labor achieved its zenith of leverage in the local political arena. Yet beginning in the 1970s, the erosion of the city’s industrial base weakened the strength of unions considerably, as manufacturing positions were slowly replaced with low-wage jobs.

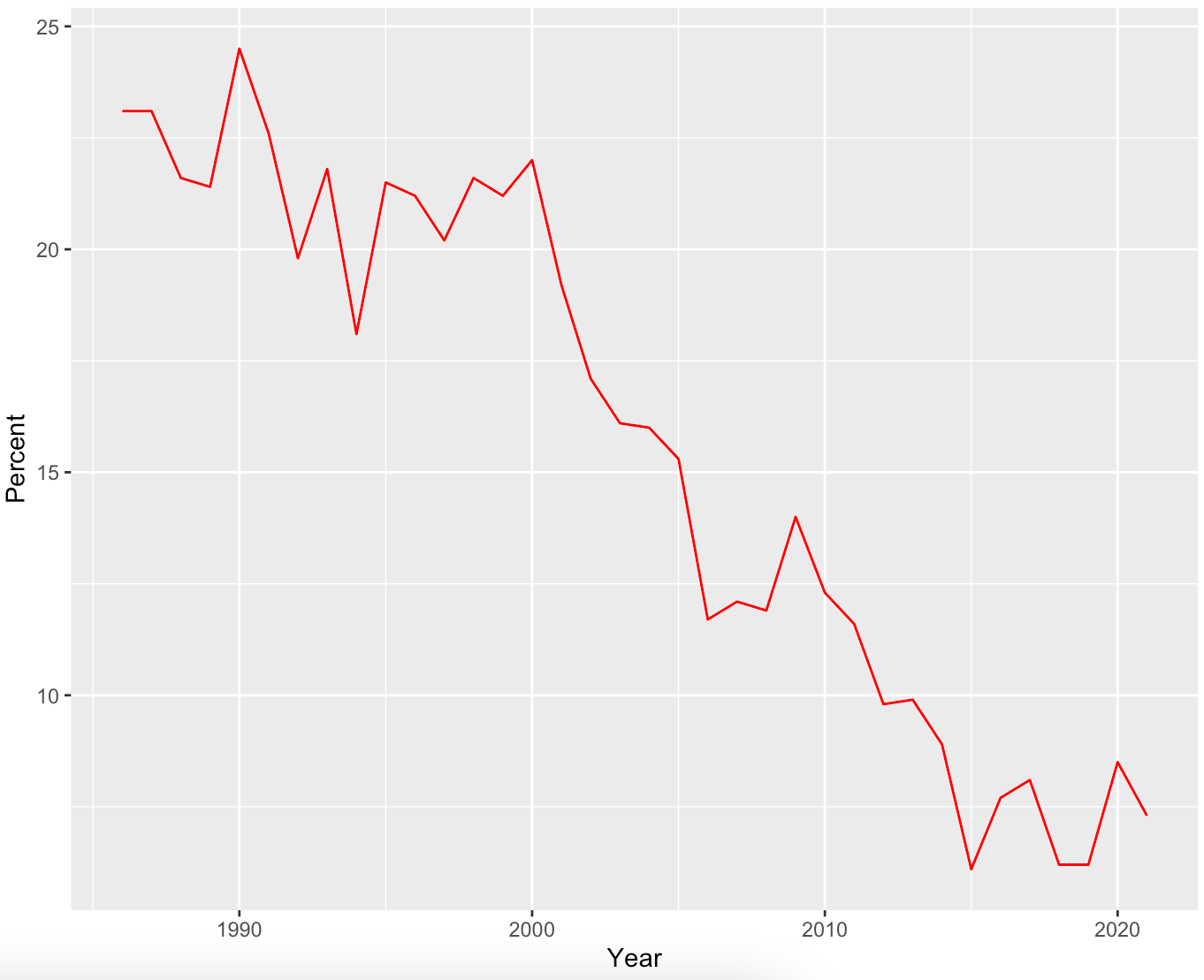

Between the 1960s and the 1990s, the membership of the Milwaukee County Labor Council had shrunk by more than a third. And while labor activists in the city pursued a variety of new strategies to build worker power, they were soon dealt another blow with the passage of Act 10 in 2011, which restricted public employees’ collective bargaining to the issue of wages and required annual union recertification elections. Several years later, Gov. Scott Walker and the state’s Republican legislators passed a right-to-work bill targeted at private sector unions. Since 2000, no U.S. state saw a greater decline in union membership than Wisconsin.

5.

The implosion of traditional parties and the assault on organized labor left the Cream City with a dramatically different political landscape for working-class politics. Organizations working to rebuild mass democracy face great odds and must work across a deep set of political trenches, in a city whose resources and power have been increasingly hijacked by the state government through statutory preemption and fiscal austerity.

Public and private sector unions remain an important force in local elections, but their ranks are greatly diminished. Meanwhile, insurgent efforts have emerged —through the Milwaukee Area Service and Hospitality Workers Organization — to organize employees who staff the glistening new downtown attractions like the Fiserv Forum.

Alongside the remnants of the labor movement were community-based organizations like Voces de la Frontera — founded in 2001 on the city’s South Side — which initially focused on raising awareness of immigrant workers needs in unionized sectors and later expanded to incorporate a combination of tactics, including candidate endorsements, voter registration drives (Voceros por el Voto was aimed at mobilizing 48,000 Latinx voters to participate in the 2018 election) and protest actions targeted at anti-immigrant policies — including an effective statewide strike campaign. The organization’s endorsement and voter-mobilization work, as one local elected official told me, are nothing short of indispensable during election season.

Nearly two decades after the founding of Voces, Angela Lang, a labor organizer who had worked in Milwaukee with the SEIU “Fight for $15” campaign and had served as Political Director of For Our Future Wisconsin, founded Black Leaders Organizing for Communities (BLOC). In 2018, BLOC — along with Voces and the Wisconsin Working Families Party — was part of a coalition to defeat Richard Schmidt, who had been second-in-command under right-wing County Sheriff David Clarke and had received the endorsement of LeadershipMKE, the powerful PAC headed by former County Executive Chris Abele. BLOC’s preferred candidate in that election — Earnell Lucas — won handily. Even if Schmidt’s relationship with Clarke — not to mention his own actions — made him an easy target, the victory was also a sign that money is not always enough to win an election.

In any case, when Lucas ran for mayor four years later, he did not receive BLOC’s support. This is because he, like nearly every other candidate in the field, could not clearly state opposition to increasing the number of police officers and, to perhaps a greater extent than other candidates, had little to say about the root causes of crime, namely poverty. BLOC understandably concluded its work in the 2022 mayoral primary without endorsing any candidate.

Also sitting out the 2022 mayoral race was the Milwaukee chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA). Re-founded after the 2016 presidential run of Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, the chapter — whose logo features a manhole cover, hearkening back to the Sewer Socialist history — has had to overcome a number of challenges. It operates with virtually no fiscal or organizational support from its national governing body (to which member dues are paid). It is largely populated by people under the age of 35, who have highly variable political tendencies, levels of experience, and interest in the electoral arena itself.

Since 2018, DSA has supported a handful of candidates for local office, and its Electoral Working Group has become increasingly formalized with each election. The chapter has built some impressive ground game — with the capacity to mobilize a prodigious number of volunteers for both door-to-door canvassing and digital engagement. Still, only one of its members — County Supervisor Ryan Clancy — has yet won local office. While the chapter mulled the question of running a candidate in the 2022 mayoral race, it opted to focus its attention on the campaigns of Eric Rorholm and Juan Miguel Martinez, two candidates for the County Board of Supervisors. Both candidates — who have racked up a series of endorsements from other groups as well — advanced past their primary elections and will be on the ballot April 5.

Yet whether the successes of Milwaukee’s working-class organizations are modest or considerable, the challenges of re-constituting a mass politics in a city that has been besieged by decades of neoliberal rule remain daunting. Since roughly 1999, the city’s growth coalition has pursued a development strategy that has emphasized place marketing and a downtown-focused property-led expansion which has only intensified gentrification and accentuated the city’s spatial inequalities. Under the New Urbanism aegis, downtown and adjacent neighborhoods thrive. One can now walk along what was once a derelict corridor of the Milwaukee River north of downtown. Cranes are a constant vertical feature of the landscape. But these blocks can also feel like a SimCity, walled off from the rest of town.

The real power players in the new Milwaukee are not working-class organizations but the real-estate developers whose PR shops promise that prosperity is yet another highrise away, the nonprofits whose program officers promise that a safer, cleaner, and more equitable Milwaukee can be accomplished with pilot programs rather than politics. This is a managed democracy — in which governing institutions, run by a small number of professionals, are legitimated by elections sanitized of conflict and participation. More voters, more problems.

6.

James Causey is standing in the worn but stately auditorium of Turner Hall, once a primary site in the organization of the city’s working-class voters. The Journal Sentinel reporter is doing a boxing-announcer routine to go along with the vintage-looking poster for the “Tussle at Turner” — the second of three debates this week.

“In this corner, standing at five foot ten, weighing 185 pounds,” Causey says. He is referring to Bob Donovan — the veteran former alderman who once told a student of mine that Milwaukee didn’t have a segregation problem and whose campaign literature depicts him sharing a drink with David Clarke, the controversial former County Sheriff who has most recently been known for peddling COVID-19 conspiracy theories.

Causey does the same routine for Acting Mayor Cavalier Johnson. While Johnson is only 35, he has already been elected as alderman twice to represent District 2, which stretches northwest from West Capitol Drive. He grew up facing urban poverty. He unsurprisingly talks about crime in terms of root causes.

The ringside bits lighten the mood. There is laughter, then applause. But the crowd, seated at round cocktail tables, is sparse. I’ve seen a larger gathering here for the band that opened for the Gin Blossoms. Within a week, the video of the event will receive just over 300 views on YouTube.

Afterwards, the Journal Sentinel will report that there really wasn’t much of a tussle this evening. And they will be right.

With most of the city’s voters likely to sit it out, it won’t be much of an election either.

Phil Rocco is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Marquette University. He is the author of Obamacare Wars: Federalism, State Politics and the Affordable Care Act (University Press of Kansas, 2016) and editor of American Political Development and the Trump Presidency (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020).

Subscribe to The Recombobulation Area newsletter here and follow us on Facebook at @therecombobulationarea.

Follow Dan Shafer on Twitter at @DanRShafer.

I have just a couple of comments/additions to what is written here. Very well done, but some missing pieces... We used to have at least two newspapers in this town, and according to my good friend and mentor Frank Zeidler, they clamored at the Mayor's office doors for any bit of news. When I ran for Mayor in 1984, it was because we were looking for a candidate to run against Henry Maier, and had formed a coalition called Committee for a New Milwaukee to do so. When no known political would run against Maier anymore, we ran me, after we/I ran, Maier, embarrassed, chose not to run again, and then the gates opened for many men who were not at all tuned into Milwaukee politics and issues to jump in the race in 1988. Getting back to my point, when we ran in 1984, every press release we wrote, every campaign event we held, got news coverage, radio, TV and newspaper, all spurred by the Sentinel morning coverage. This mattered. Also, Frank would say that political organizing happened at the bus stops. The automobile killed that. But, when I ran, we had strong neighborhood organizations, one of which I worked for, and local politics did matter. Most of those are gone now. Finally, do you remember when they had those card stock paper signs up on the telephone poles, with all the registered voters listed and their ward numbers and polling place? These were everywhere, and encouraged voter participation and registration. We should bring this back! Please send this along to Phil Rocco. Thanks! Donna Horowitz Richards, now living in Fond du Lac.

This was brilliant. Thanks for this!