CHART: The huge differences in changes to state aid in Assembly Republicans' shared revenue plan

Spoiler: It's not great for Milwaukee.

The Recombobulation Area is a six-time TEN-TIME Milwaukee Press Club award-winning weekly opinion column and online publication written and published by veteran Milwaukee journalist Dan Shafer. Learn more about it here.

This is a guest column by Phil Rocco, associate professor of political science at Marquette University. Rocco has been a regular contributor at The Recombobulation Area.

Republicans in the Wisconsin State Assembly have released their bill on revamping the state’s broken shared revenue system.

It’s a big, gnarly, complicated bill, and here at The Recombobulation Area, there’s a lot we’re going to be looking into to break this thing down in the days and weeks to come.

But one of the highlight items that has been reported on in the run-up to this bill’s release is on how the plan would be applied differently to municipalities of differing populations. As JR Ross at WisPolitics reported weeks ago, the “shared revenue plan under discussion would weight the formula for new $ to help smaller communities more.”

With the draft of the bill now released, we’ve been able to determine just how much more.

Strings Attached

Before we get into how new shared revenue is distributed, let’s first look at what that new aid is and how governments are allowed to spend it.

For starters, the proposed legislation allocates $227 million in supplemental revenue sharing for local governments, more than three quarters of which is directed at municipalities, with the remaining share reserved for counties. Yet unlike funds provided under the current municipal and county aid program, these new supplemental payments could only be used for “law enforcement, fire protection, emergency medical services, emergency response communications, public works, and transportation.” The use of supplemental county and municipal aid payments for administrative services (and other needs) would be prohibited.

There’s also another important limitation, which applies not just to the new supplemental aid payments included in the proposed legislation, but to all existing revenue shared under the County and Municipal Aid program. Section 59 of the proposed legislation creates a new maintenance of effort requirement which specifies that cities, villages, and towns with a population of greater than 20,000 must “certify to the Department of Revenue” that they have “maintained a level of law enforcement that is at least equivalent to that provided in the city, village, or town in the previous year” or else they risk losing 15% of their total municipal aid.

How will this be enforced? In general, local governments must prove that they are both spending the same amount on law enforcement as they did in prior years and engaging in the same amount of law enforcement (for this part, governments must prove that they are doing two of the following: making the same number of arrests, issuing the same number of traffic citations, or employing the same number of full-time officers). So, in short, this bill isn’t merely a technical update to the County and Municipal Aid Program, it imposes significant new terms on the fiscal relationship between the state and local governments.

How Local Governments Fare Under the Supplemental Aid Proposal

To analyze how local governments fare under the supplemental aid proposal, it’s worth remembering that Wisconsin’s century-old system of shared revenue––designed to compensate local governments for the state’s preemption of major tax bases––is broken. In recent decades, the state legislature has simply refused to increase aid to local governments in tandem with inflation. Thus while City of Milwaukee residents send an ever-growing share of tax revenue to the state, the city’s shared revenue actually declined in nominal terms from $235 million in 2000 to $218 million in 2022. Had shared revenue kept pace with inflation, Milwaukee would be receiving nearly double the payment it received in 2000. In an interview with The Recombobulation Area during last fall’s budget process, new budget director Nik Kovac said this essentially amounted to an annual $150 million budget cut from the state.

Given this extreme policy drift in County and Municipal Aid, the question is how do local governments fare under the new supplemental aid payments when compared to the current shared revenue payments they are receiving from the state? While all local governments receive at least a 10%increase in aid, a quick look at the data suggests that gains from the new supplemental aid payments would not be equally distributed across the state. On the one hand, more than a dozen municipalities would see increases in aid of over 1,000%. The town of Popple River, in Forest County, would see an increase in aid that exceeds 5,000%. Popple River has a population of 43. To put this in terms of the actual dollar amounts, today, it receives $14.09 in municipal aid per capita. Under the new arrangement, it would receive $729 per capita.

Many more local governments would see increases of only 10%. For Green Bay, that would mean an increase from $145 per capita to $160 per capita. One might reasonably conclude from this that, under the new arrangement, it pays to live in Popple River.

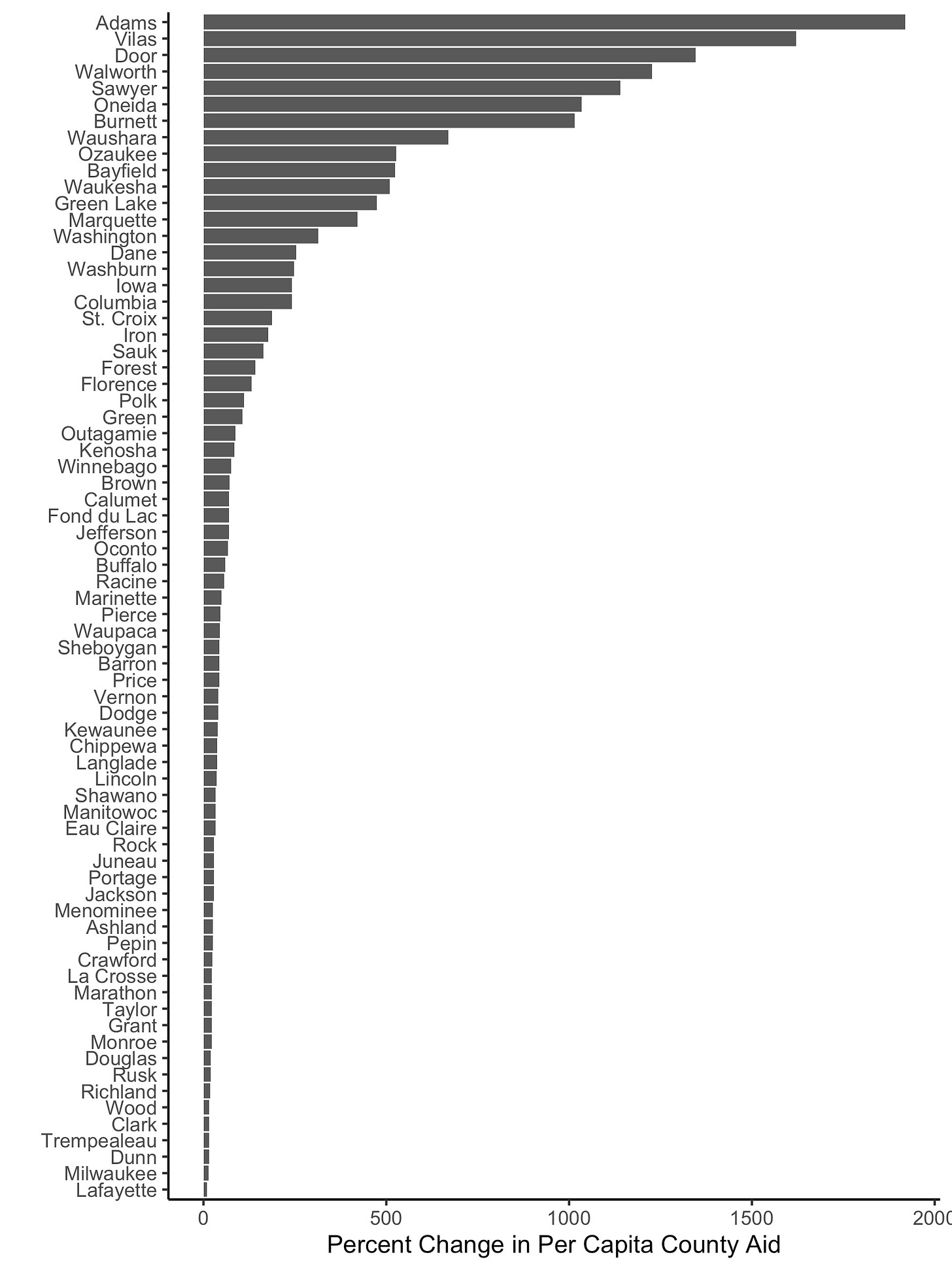

The charts below illustrate what happens across the state. First, we see the percent change in per capita municipal aid, aggregated at the county level.

Next, we see the percent change in per capita aid to counties. The reader will notice that both charts show that Milwaukee County ranks at the bottom of the distribution.

We can also see disparities in aid increases when we drill down to the municipal level. The chart below shows the percentage increase in municipal aid for municipalities in Milwaukee County. Here we can see that while relatively high income municipalities like Fox Point, River Hills, and Whitefish Bay receive a large boost in aid, the cities of Milwaukee and West Allis — which have among the lowest household incomes in the county — receive the smallest increases.

The bottom line here is that not only does the new Local Government Funding bill come with significant new strings attached, it does not evidently solve the problem created by decades of stagnation in the state’s shared revenue system.

Phil Rocco is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Marquette University. He is the author of Obamacare Wars: Federalism, State Politics and the Affordable Care Act (University Press of Kansas, 2016) and editor of American Political Development and the Trump Presidency (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020).

Subscribe to The Recombobulation newsletter here and follow us on Facebook and Instagram at @therecombobulationarea.

Already subscribe? Get a gift subscription for a friend!

Follow Dan Shafer on Twitter at @DanRShafer.

I would be interested in some more detailed explanation on just what about the bill's formula is driving these differences. It seems pretty random. Is it just smaller municipalities get more supplemental aid? What is the state aid formula based on in the first place, if it's not just per-capita?